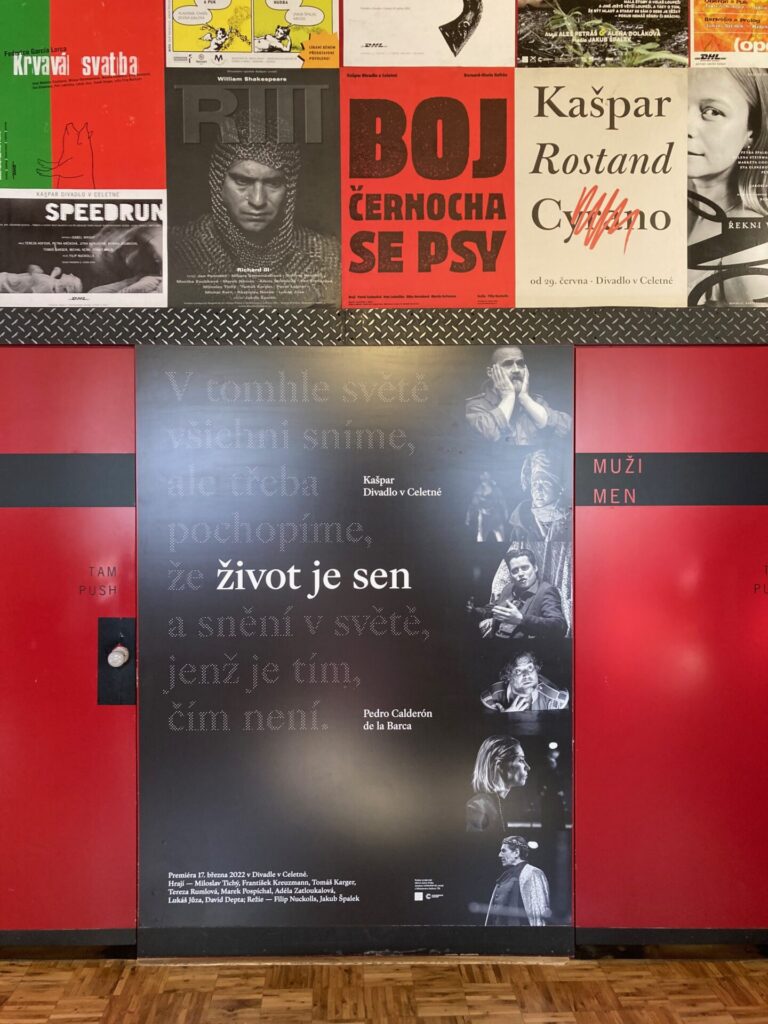

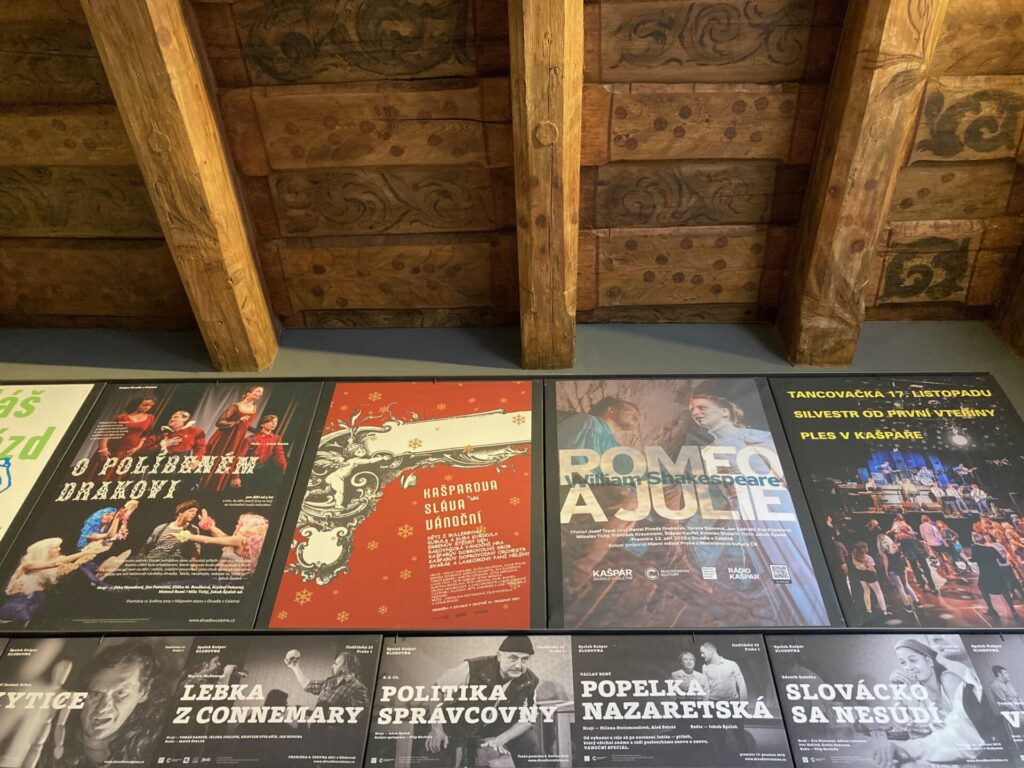

Tourists lining up in front of the entrance to the medieval pub U Pavouka (At the Spider) on Celetná Street are mostly unaware that they are standing in the courtyard of a palace dedicated to theater. A large part of this house, Menhart Palace, houses the Theater Institute, the most significant Czech documentation, organizational, and scientific center of Czech theater. It is also home to the Celetná Theater, where the Kašpar Theater Club, one of the best theaters in Prague, has been performing for several decades.

And they probably don’t even know that on the palace’s first floor you can spend a pleasant time in the theater cafe, which, along with many other cafes in Prague theaters, is a specific type of cafe.

Waiting tourists are guarded by a wooden statue of Heracles With a Lion at the staircase to the theater, most likely created by Jan Jiří Bendl, the most important Czech early Baroque sculptor, who was the sculptor of the statues on the Marian Column on the nearby Old Town Square or the St. Wenceslas Column by the Charles Bridge, where you can still see the pavement from the original Judith’s Bridge, the predecessor of the Charles Bridge.

Nowadays…

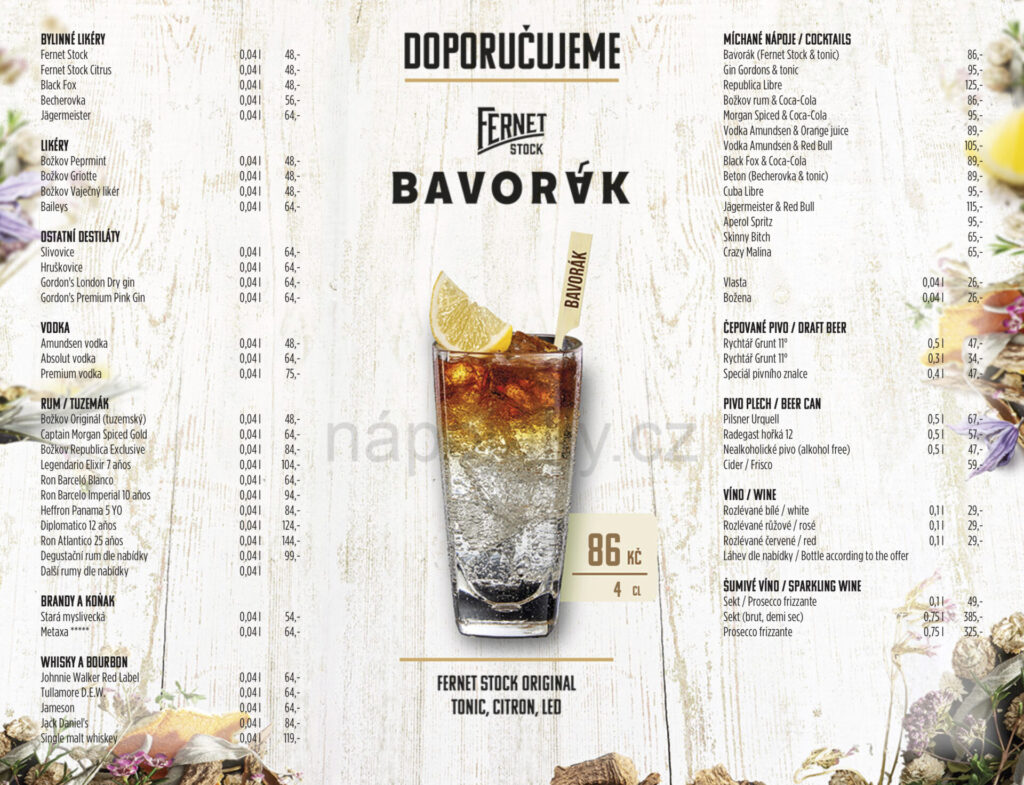

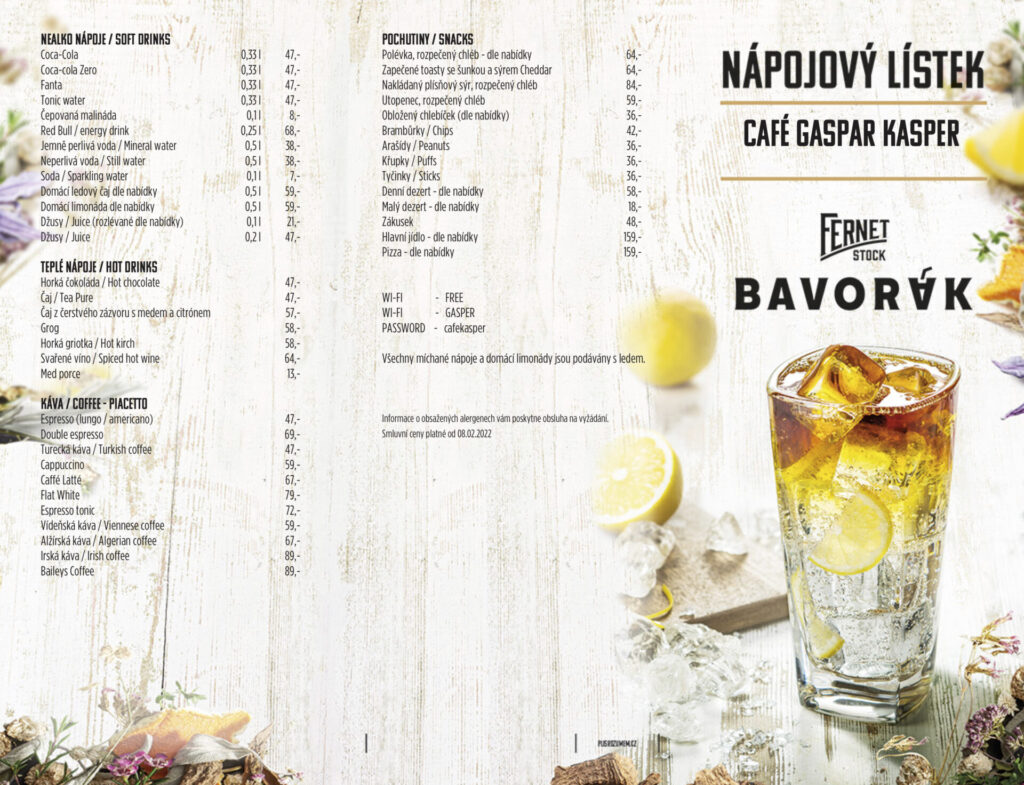

The cafes of Prague theaters have a specific ambiance where it is always pleasant to be. You can only go there for a “snack-like” lunch – you won’t get goulash or beef sirloin with cream sauce and six dumplings there. But you won’t go hungry (look at the offer of the theater cafe in Celetná). Mostly expect sandwiches, soup, baked toast, some sort of cheese, chips, and salted nuts or breadsticks. Regarding drinks, theater cafes are full-fledged – from coffee of many kinds, through lemonades and juices to beer, wine, and spirits.

Theater cafes are often very cheap (a glass of 1 dcl wine for 29 crowns in the very center of the city is really not a standard price). This has to do with the fact that many theaters – including this one – are not commercial. They have a founder who contributes to their activities. And this financial help is reflected in the prices of tickets for performances and in the prices of their cafes, which often serve as a theater club for the theater ensemble.

But the more important thing is that such cafes are imbued with culture and that it is enjoyable to spend time there almost any time of the day – this cafe is open from 9:30 a.m. (Theater companies are also happy about this – in Czech theaters, new productions are traditionally rehearsed from 10 am to 2 pm). On weekends, the cafe is open from two in the afternoon. Therefore, don’t hesitate to visit this wonderful ambiance at any time – they are open until 6 pm because then the cafe is also then available to the spectators who came to see the performance.

And once upon a time…

The Menhart Palace was built around 1700 on the site of several medieval Renaissance houses. The palace covers the entire depth of the block between Celetná and Štupartská Streets – opposite the passage to Štupartská Street is the house where Charles IV was most likely born.

The palace is one of the most beautiful buildings on Celetná Street; its baroque facade is one adornment of the Royal Route you cannot miss. The first building records in this place date back to 1402 when a house called U Koz (At the Goat’s House) stood here.

At the beginning of the 18th century, the palace was bought by Jan Bedřich Menhart. Thanks to him, a theater was performed here as early as the mid-18th century. However, this was not permanent, and it was still a long way from that era to the current Kašpar Theater Club. But since then, the palace has had its name.

The most famous owner of the palace – diplomat, music composer, traveler, adventurer, warrior, savior of the Emperor’s life who was beheaded in front of thousands of spectators at the age of 57

At the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, the house was owned by Kryštof Harant from Polžice and Bezdružice who was one of the 27 lords executed in the Old Town Square after the defeat at the Battle at White Mountain.

Kryštof was a nobleman and an important man of his time. (For his better “historical placement,” it is good to remember that he was born in 1564, the year that William Shakespeare and Galileo Galilei were also born, and the year that Michelangelo Buonarroti died.)

Kryštof Harant came from 13 children. A significant influence in his life was his father Jiří, who gave all his children the best education available. For Kryštof, this meant, among other things, that at the age of thirteen, his father sent him to Ambras Castle in Innsbruck to the service of Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria. Kryštof lived here for eight years – he learned etiquette, was educated in music and literature, and improved in foreign languages, geography, astronomy, and political science. He was not only manually skilled but also artistically and musically gifted; he also excelled in the important sports of the time: fencing, swimming, and horse riding.

The adult Kryštof Harant was not only a diplomat but also a writer, a traveler (he also went on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela), and an outstanding music composer. He spoke seven languages, knew geography, and studied history. He visited the Mediterranean and Israel, while also sailing on the Nile in Egypt. When he saw a hippo for the first time in his life in Africa, he wrote in his notes: “Another strange animal. A water horse that also supposedly eats people.”

Kryštof Harant was also a brave man – when he was attacked by robbers on his travels, he defended himself and managed to bury a pouch of money in the sand so that he was not only not killed but also not robbed.

He experienced many things on his travels, which he described in his travelogue. Very detailed, which is already indicated by its title: “Wandering, or the Journey from the Kingdom of Bohemia to Venice, thence to the Holy Land, the land of Judah and on to Egypt, and then to Mount Oreb, Sinai and St. Catherine’s in the desert of Arabia,” but also by its scope (only the first volume has almost 400 pages).

(The Czech version can be viewed and downloaded free of charge on the Prague Municipal Library website.)

An exciting moment in Kryštof Harant’s life was when he saved Emperor Rudolph II’s life. He was then employed as an imperial chamberlain. One evening, the Emperor began to choke during dinner, and being aware, Kryštof shook him for so long and so hard that he finally shook the lodged bite of food out of him. Grateful for saving his life, the emperor doubled Kryštof’s annual salary.

Despite this, however, after the death of Rudolph, the Habsburg monarch and a Catholic, Kryštof converted to the evangelical faith and even joined the rebellion against the Habsburgs. After the defeat at White Mountain, Kryštof returned to his castle, Pecka, and although he had the opportunity to flee abroad, he made no attempt. He did not believe that he was in greater danger.

He would come to regret his decision very much – he was executed at the infamous Old Town Execution as the third in line. Concerning this mass execution, let it be said that no execution block was used. The condemned man was kneeling with his hands behind his back with the executioner standing behind him. The executioner swung his sword in a horizontal direction, and when the sword hit the condemned man’s neck, the executioner dragged the sword towards himself because the head had to be cut off completely; it could not even be left hanging by the skin. The most famous Czech executioner, Jan Mydlář, who was 49 years old, led the execution on the Old Town Square. (He died at the age of 91, and his son and two grandsons, one of whom was eventually executed, also worked as executioners.)

Jan Mydlář was a merciful executioner. He allowed his victims to pray before the execution and raised the sword only when it was clear that the condemned was ready for the act. The advantage for the condemned was that Mydlář had studied medicine at Charles University in his youth, so he knew how to properly behead someone. During the trial, Kryštof Harant received a significant privilege – he was not tortured during his imprisonment, his head was not impaled on a stake, and his wife was allowed to bury his body. This could be considered as a privilege for his services to the Habsburgs in the past.

The fact that fate can be unpredictable was also confirmed in Harant’s case. His friend and former brother-in-law (Kryštof was married three times His first two wives died) Heřman Černín from Chudenice undertook the incredible journey to the Holy Land and other far-off regions (yes, that same journey about which Kryštof wrote the many-hundred-page travelogue). Many years after their adventurous journey together, Heřman helped to imprison Kryštof Harant and later watched his execution. Then, he married Kryštof’s widow and acquired Harant’s castle, Pecka, and its manors. In assessing this injustice, we can take satisfaction in the fact that he was apparently unaware that while Harant’s wife, Anna Salomena, was rich and very commercially efficient, she was also domineering, emotionally unstable, and very moody.

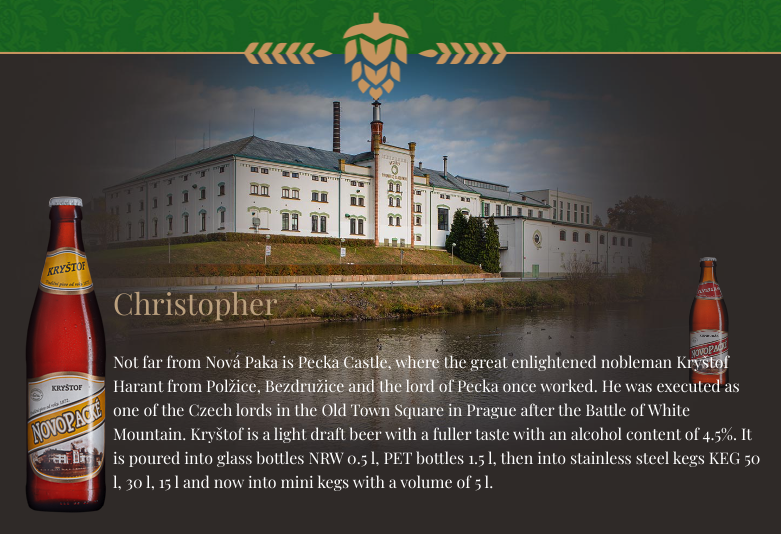

Kryštof Harant was not only a good householder but also kind and nice, unlike his wife. That is why the people of Pecka and the adjacent estates liked him. This is evidenced by the fact that in the town of Pecka, there is a sports club called Harant, or that in nearby Nová Paka, the local brewery produces the popular Harant beer.