The future factory manufacturer Josef Volman was born in 1883 into the family of the owner of a workshop to produce agricultural machinery. At the age of eighteen, he set out on his first trip to America, returning there in 1907 for a three-year stay to learn American entrepreneurship and the art of management. He lived in Chicago, where he studied chemistry and engineering, and where he also met his future wife, Ludmila, in the Czech community (they later discovered that they had come to America on the same boat).

In 1911, he founded a small engineering company, but its development was hindered by the First World War, during which Josef Volman enlisted and fought at the front in Serbia, Italy, and Russia. When Josef was captured, his wife obtained a passport to leave the country under the pretext of a business trip and went alone to the war zone in Romania. In May 1915, they met again. Josef Volman later wrote about it with admiration: “When she arrived there, she was received more spectacularly than the greatest war hero. All the generals, the entire staff, and all the officials down to the porter hailed her as the model of a heroic woman who did not shy away from the dangerous journey across several countries to follow her husband into the tumult of war.”

After the war, they expanded the company and the family together – in 1920, the couple had a daughter, Luďa. The company prospered, but tragedy struck Josef Volman in his personal life. His beloved wife died at the end of 1933 at the age of 44. Josef Volman went with his daughter on another trip to his beloved America to banish his sadness.

Villa for a Million

Josef Volman was a visionary who believed in his idea. This is how he built an engineering company “from scratch”, which in the early 1940s employed 3,000 people and 300 apprentices with sales offices in 35 countries (for a closer idea – in 1940, Čelákovice had a population of roughly 5,000).

Josef Volman had a good reputation in the town – he was a good person and patron who generously supported various associations in his town and cared about the development of Čelákovice. His factory had a modern factory kitchen and canteen for the employees; he built houses with rental apartments for them. Josef Volman built a sports stadium for employees to improve their leisure time. He supported the sports club, which boasted 1,800 members.

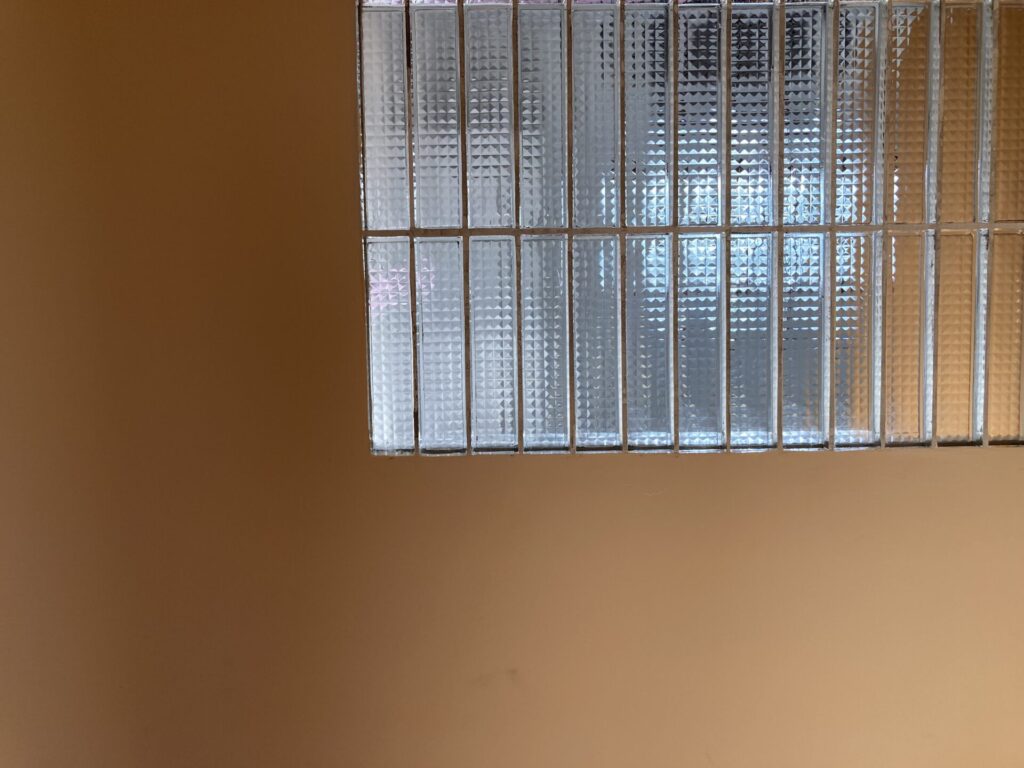

At the end of the 1930s, Josef Volman decided to build a modern villa. This resulted in one of the most interesting buildings of functionalist architecture in Europe in the late 1930s. The house had a reinforced concrete skeleton and monolithic reinforced concrete ceiling slabs. The exterior walls and internal partitions were made of hollow concrete blocks.

The house was initially supposed to have two luxfer glass walls; the third wall on the ground floor was added to the project later. That’s because Josef Volman wanted a house costing exactly one million crowns. There was still something missing in the construction costs, and after the third luxurious wall was built, the final bill was exactly one million crowns. (To understand this amount, it is good to know that in 1938, the average salary of a middle-class civil servant was 20,000 crowns a year. So, for the average citizen, it would equal their wages for 50 years.)

A Safe Background in Turbulent Times

The new house was exactly according to its owner’s imagination — luxurious housing as well as a representative space for a successful engineering company. The house stands on a large plot of land, which also allowed horse riding. The garden was carefully designed as a park; it also had a swimming pool and a tennis court. The building permit was issued in August 1938, and the villa was completed ten months later, only a few months after the outbreak of World War II…

In 1941, Luďa Volmanová married Jiří Růžek, who became a procurator in his father-in-law’s company. In 1943, Josef Volman died, and thousands of his employees walked in the funeral procession. Jiří Růžek completely took over the management of the company and, together with his wife, continued to financially and materially support the Czechoslovak resistance until the end of the war.

However, the relief after the end of the war did not last long. A few months after the end of the war, Josef Volman’s engineering company was nationalized.

Post-War Nationalization and Why It Was Much More Massive Here Than Elsewhere in Europe

The economic crisis of the 1930s and the post-war rise in the influence of left-wing political parties throughout Europe led to reflections on the end of capitalism and its replacement by a “fairer” order of society. In large industrial enterprises, workers were radicalized and demanded property changes in favor of state ownership so that the socially weak classes would be secured. The demand for nationalization was also contributed to by the fact that many enterprises were in such bad shape after the war that private capital was insufficient to rebuild them.

At that time, nationalization was on the agenda of all political parties. However, they fundamentally differed in the extent to which they wanted to apply it. The general consensus was only on the confiscation of traitors’ property, which had already been discussed by the exiled government in London and also by domestic resistance.

It was a disaster for Czechoslovakia after the war that it was included in the Russian sphere of influence. At that time, a so-called system of regulated democracy was established in our country. This happened after the signing of a document called the Košice Government Program, prepared by the communists. (It was declared that it was signed on April 5, 1945 in Košice, but in fact it had already been signed on March 29 in Moscow.)

The program was very radical. It aimed not only to restore the national economy devastated during the war. It was also to lay the foundations of a new social policy in favor of “all classes of the working people” and to transfer the property of “Germans, Hungarians, traitors and collaborators” to national administration, except German and Hungarian anti-fascists. The government envisaged land reform, as well as the fact that it would “bring the traitors from among banking, industrial and agricultural magnates to justice with all determination” and that it was necessary to “build the entire monetary and credit system, key industrial, insurance, natural and energy enterprises resources under general state management”.

The Košice Government Program was called the program of the national and democratic revolution. It spoke of the collective guilt of right-wing parties, the German and Hungarian population for the breakup of Czechoslovakia and cooperation with the Nazi regime. It also defined the principles of interventions in ownership relations and the foreign policy orientation towards the Soviet Union.

In directly quoting the text: “Our relationship with our biggest ally – the USSR, will be completely built up in the cultural aspect as well. To this end, everything that was anti-Soviet will be removed from our textbooks and teaching aids. The youth will also be properly educated about the USSR. Therefore, Russian will be in the first place in the new foreign language curriculum. Care will also be taken to ensure that our youth acquire the necessary knowledge about the origin, establishment, development, economy, and culture of the USSR. New teaching programs will also be established at the universities for this purpose: history of the USSR, economics of the USSR, and law of the USSR.”

Deprivation of Citizenship and Deportation to Germany

In Czechoslovakia, nationalization was ordered by decrees of the president of the republic, which even preceded the establishment of the provisional parliament by a few days (October 28, 1945). Key and large industries, such as the food industry, banks, and insurance companies, were nationalized. The production capacity of nationalized enterprises accounted for almost two-thirds of Czechoslovak industry. All this was preceded by the August nationalization of the film industry, including the import, export, and distribution of films.

However, in May and June 1945, the confiscation and settlement decrees of the president of the republic entered into force, confiscating the property of Germans, Hungarians, traitors, and collaborators. Then, at the beginning of August 1945, President Beneš issued a decree by which Germans living on Czechoslovak territory had their citizenship revoked and were subsequently deported to Germany. They were primarily residents of the border areas, the so-called Sudetenland, from where the Czechs had to leave after the Munich Agreement. (At that time, about 170,000 of them went inland, and half a million, often in mixed marriages, remained in Sudetenland. They lived as second-class citizens, but with a better status than the Jews had.) Revoking their citizenship was followed by the displacement of Czech Germans. Each person was allowed to take 50 kg of property and one thousand Reichsmarks. An estimated 1.6 million people were evicted to the American occupation zone of Germany and 800,000 people to the Soviet zone.

Compensation was provided for nationalized property either financially, in securities, or in some other way – and, of course, one can ask what part of the real price of the nationalized property this compensation was. However, compensation was only granted to Germans or Hungarians who proved that (in the words of President Beneš’s decree): “remained loyal to the Czechoslovak Republic, never committed crimes against the Czech and Slovak peoples, or either actively participated in the struggle for its liberation, or suffered under by Nazi or fascist terror”.

Extreme Pressure After the Communist Putsch of 1948

The Czech Left, communists, and social democrats are responsible for the extraordinary scale of nationalization of the economy in Czechoslovakia. President Beneš complied with them to calm the atmosphere in the post-war republic. He thus strengthened the left and thereby de facto eased the way to the Communist putsch on February 25, 1948. (Part of the way to this putsch was the rejection of the Marshall Plan or European Recovery Plan, thus US economic aid in 1947.)

On that day, our already incomplete democracy ended, and totalitarianism was established. Although the post-war nationalization was supposed to end with Beneš’s decrees, after the February Putsch, there was a complete liquidation of private businesses and family farms. Communists called private entrepreneurs class enemies, parasites, and black marketeers. Their property was also confiscated mercilessly.

However, the repression and pressure of the state gradually affected small craftsmen and traders as well. A separate sad chapter of Czech history after the communist putsch was the forced collectivization of the countryside following the model of the Soviet collective farms. Farmers were forced to give their property to agricultural cooperatives, in which all members farmed together. Tens of thousands of farmers were sentenced to prison under various pretexts, their families were displaced and they were forbidden from living in their original villages.

Those who did not want to acquiesce were ordered to submit meat, milk, and other agricultural products from the state. The levies were gradually increased until they could not be met. Those who did not comply received fines, punishments, imprisonment, and eventually confiscation of property.

Confiscation of Property, Emigration, and First Permitted Shower in Eight Months

February 25 was also an important day in the life of Jiří Růžek, who led the family engineering company after his father-in-law’s death until it was nationalized. Czechoslovak State Security arrested him, the family’s property was confiscated, and the villa was placed under national administration. In the justification of the request for the introduction of the national administration, it is said, among other things: “People who did not have a positive relationship with the People’s Democratic Republic met in this villa, for example, on the night of February 21 to 22. From there, hate speech against the People’s Democratic Republic was spread.” The villa was confiscated, and the family was evicted.

From Jiří Růžek’s diary: “My wife Luďa Růžková – Volmanová left Czechoslovakia with our children in 1948 without a single penny and with only one spare piece of clothing for her and the children aged 4 and 6. Nothing of the former “Volmanka”, the family joint stock company, belongs to us now, despite the will of the founder and father-in-law Josef Volman who clearly stated it should be passed down to our children undiminished.”

Jiří Růžek did not have time to emigrate: “From May 14, 1948, I was in pretrial detention for 18 months, mainly at the regional court in Cheb in several prisons, almost all of which contradicted the basic rules of humanity – eleven people in a single-person cell, the first shower allowed after eight months. Fasting every other day and a hard bed, through New Year’s 1949 without heating and with a punched-out window with one blanket on boards on a cement floor.”

After serving his sentence, he worked as a worker in smelters; he was allowed to meet his family only after 20 years when the regime was relaxed in 1968. He was then allowed to visit them in France.

In 1952, a kindergarten was established in Josef Volman’s villa for the children of his nationalized engineering company employees. The kindergarten chronicle: “In December 1952, the local national committee decided to open a third kindergarten in Čelákovice. The beautiful villa of former factory owner Volman was chosen for this purpose. A luxury that once served one wealthy individual now serves the children of working mothers.”

Rudé právo (the Red Justice), daily newspaper of the ruling Communist Party, June 2, 1960: “In the magnificent residence that the manufacturer Volman had built in Čelákovice, next to the factory, just before the war, there is today a beautifully established kindergarten for 74 children. They don’t live in someone else’s residence, but in their own, because the villa was built from the calloused hands of the grandfathers of today’s children.”

Rebirth of the Jewel of Functionalist Architecture in Europe

Luďa Volmanová – Růžková died in Germany in 1982 at only 62 years old. She did not live to see the Velvet Revolution nor the subsequent restitution of property. The villa was acquired by her husband in 1990 in restitution. However, the once magnificent villa was now only a shadow of its former glory. It was abandoned and quickly fell into disrepair. And what time, weather, and zero maintenance did not cause, thieves and vandals did. Jiří Růžek was returned only a ruin.

Fortunately, the owners of the CZ.TECH company fell in love with the reputation and beauty of the villa. Their company is not only based in Čelákovice, but even do business in the same field as Josef Volman. The reconstruction was thorough and expensive and, therefore, also very long. It started in 2002, and a lot of time was spent studying the archives and preparing for the reconstruction. However, the result is phenomenal – the project quite rightly won the Jury Prize for the sensitive reconstruction of a devastated monument in the Construction of the Year 2016 competition. Subsequently, the narrative monograph Volman’s Villa – a Jewel of Interwar Architecture was also published. Volman’s villa became a member of the prestigious Iconic Houses network.

No one lives in the restored villa today, but that does not mean that it is not alive. You can take a guided tour and see for yourself. You can come here for a theater performance or a concert. You can experience a unique sleep under the stars, where you will enjoy excellent gastronomy, music, and yoga lessons – but above all, you will sleep on the terrace of Volman’s villa, with the sky above your head. Or you can book the villa just for yourself and experience a truly extraordinary wedding night there.

The villa and its genius loci will truly amaze you…

(The blog was written with the help of information.)

By the way – Čelákovice is just outside Prague, accessible by public transport. For a faster way there, we can recommend the taxi service Svez.se, a partner of our movie Kevin Alone in Prague. (The story of a thirteen-year-old boy, a Czech-American, who comes to discover Prague through the stories of its monuments.)