The first state formation on the territory of today’s Czech Republic, which we have at least some concrete and verified information about, was the Samo Empire, whose origins date back to the year 623. Czech history is sparse for words about who lived, hunted, grew crops, were born and died “with us” before this era.

However, we know that the oldest remains of human presence in Bohemia dates back to about a million years BC. They are roughly worked stone tools that were found in 1984 during the construction of a highway near Beroun (this is a former royal city located a short distance west of Prague. The first documented mention of settlement in this place dates back to 1088).

The oldest skeletal find, the jawbone of a Neanderthal child from the Šipka Cave (the Dart Cave) in Moravia, dates back to an unspecified period of 300,000-40,000 BC. It is also the oldest evidence that our ancestors used caves for living.

Then came handling fire and the ability to build homes. People moved to follow game, building a base camp with permanent living quarters with a fireplace, and a water source, and temporary habitats around the perimeter of their current hunting grounds.

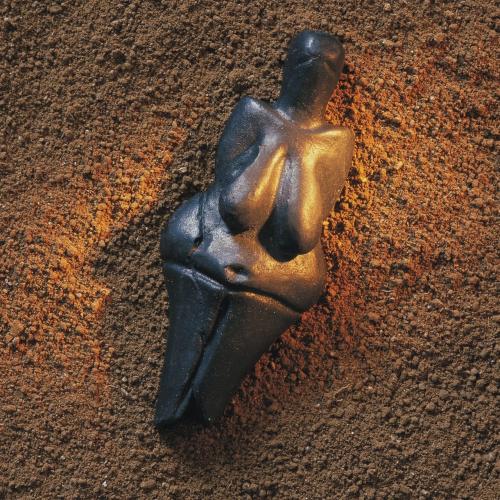

From the period 29,000-25,000 BC, we are commonly introduced to the Venus of Věstonice, a naked woman figurine made of baked clay, which is the first evidence of artistic feeling and worship of a cult.

In the following period, our ancestors hunted more fish and birds, gathered fruits and seeds due to climate change. They discovered the bow, the harpoon and the spear thrower. And they increasingly transitioned towards a more sedentary way of life. Later on, our ancestors became not only gatherers but also growers. They grew wheat, millet, barley, as well as peas, lentils, flax and hemp. Their diet included purpose-grown apples, cherries, plums, onions, and carrots.

Then came the domination of metalworking and, at a similar time, cannibalism. This came partly as a “food need”, but mainly as a result of the belief that the abilities of the one eaten would be passed on to the person…

We are already in the Early Iron Age, when Celts settled in the territory of the present-day Czech Republic. (Despite the fact that we are often referred to as a Slavic nation, only 35% of Czechs have Slavic genes in their DNA. In addition to the Celts, the Germans also left a significant mark on our DNA – after all, our history is most intertwined with today’s Germany and Austria.)

It is the Celts to whom we owe the name Bohemia. One of the sixty or so Celtic tribes that lived here in 400 BC were the Boii. They named their territory Boiohaemum, i.e. Bohemia. (The genetic proximity is also interesting, as the so-called “Celtic gene” has been identified in Bohemia, one area of Austria, part of Brittany, and in Great Britain and Ireland. Therefore, we share the G551D mutation of the CFTR gene [cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator], which is the cause of the disease cystic fibrosis.)

By the way, the area around Beroun is also interesting because one of the essential Celtic oppida (fortifications) in the Czech territory was built in the nearby village of Stradonice in 120 BC, and the castle in the neighboring village of Nižbor is now an information center of Celtic culture.

The first reliable mention of Slavs in our territory dates back to 535. A few decades later, at the beginning of the 7th century, the legend of the Grandfather Czech is dated. And then we are in the time of Prince Samo and his empire.

At Least Charles IV and Maria Theresa

Starting with Prince Samo, 67 monarchs ruled the territory of which we were a part. (The borders of these state entities were not identical to our borders today. They changed over the centuries, including the fact that there were times when we also had “domestic” access to the sea.)

Although the succession of these princes, kings and emperors is part of the history lessons at primary school, with a probability bordering on certainty it can be expected that most Czechs would be able to name ten, perhaps fifteen, of these rulers. With equal probability, however, it can be argued that even if they didn’t remember anyone else, they would all include Charles IV and Maria Theresa in this list.

Maria Theresa is the only woman to have been the head of state in our entire history (including the republic period since 1918). Everyone knows about her at least that she introduced compulsory school attendance and had sixteen children, but there are many more important and interesting things in her service to the country (she ruled from 1740 to 1780) and her personal life.

Reforms of Maria Theresa

Maria’s father and predecessor, Emperor Charles VI, wanted the succession to be left to his children. That is why he issued the Pragmatic Sanction on the Succession of the Most Excellent Dominion of Austria in 1713, which guaranteed the succession in the female line in the event of no male heir. This proved to be very wise. Although the first child of Charles VI was Leopold, he died at the age of seven months. Then Maria Theresa was born, followed by two more daughters.

Although the pragmatic sanction was accepted by all important European states, as soon as the twenty-three-year-old Maria ascended the Czech throne, others claimed the succession. Although Mary was supported by Britain and the Netherlands, she still did not avoid a military solution to the situation. Peace and recognition of Maria’s claim to the throne came after eight years of war.

At a time when no one questioned Maria’s claim to the throne, she embarked on fundamental reforms. A central administration of the country with professionally trained officials was established, political and judicial power was separated, land registers were established, a single currency was introduced, a criminal code was drawn up, and a statute labor patent was issued, which shortened the labor and graded it according to the amount of land tax paid by the state’s subjects. (The statute labor was completely abolished by Maria’s son, Joseph II. He also issued the fundamental Patent of Tolerance in 1781, which legalized religions other than Roman Catholicism.)

Prague Castle also underwent major changes, which Maria Theresa had rebuilt into a representative residence of the Czech king – part of this so-called Theresian reconstruction of the Castle included filling in the moat that separated the Castle from Hradčany Square, and the construction of the first courtyard of the Castle. A not insignificant part of the reforms was the introduction of house numbering, which Prague had implemented even earlier than Paris.

Everybody to School!

A significant breakthrough was the introduction of compulsory school attendance. Maria Theresa was led to this by the belief that better education for the population would lead to increased prosperity for the state. The goal was for all residents to be able to communicate through written or printed text. This was mandated by a document called the Theresian School Regulations, which was issued on December 6, 1774. Two points from its text read:

“In all the smaller towns and cities, and in the countryside (at least in those places where there are parish churches or branch churches near them), general or so-called trivial schools must be established, in which the children will be taught religion or its history, as well as ethics, the knowledge of letters, syllabification, and the reading of printed and written texts, the four kinds of arithmetic, and the simple trinomial. Nor will they be forgotten to teach them how to manage their affairs and run their economy using acquired knowledge, skills, and principles suitable for everyone in every life situation.”

“When setting up classrooms, care must be taken to ensure sufficient access to light and adequate space for the appropriate number of schoolchildren. Classrooms must not be too large, so as not to use up a lot of firewood in winter, but also not too small, as it is necessary for all pupils to sit comfortably. They must be equipped with the necessary number of benches, tables, blackboards, inkwells, and other accessories, as well as a compartment suitable for storing books…”

The Empress, the Grandmother of Europe, and an Interesting Coincidence of Numbers

The Pragmatic Sanction guaranteed Maria Theresa the rule only in the Habsburg hereditary lands – Bohemia, Austria, Hungary and several other smaller territories. So although she was also called an empress, she never was one, because she could not be. The emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation was her husband Francis I Stephen of Lorraine, and after him, their sons Joseph II and Leopold II. The last emperor was Leopold’s son Francis I, who renounced this title in 1806. The Holy Roman Empire, a constantly changing confederation of unequally sized political entities, thus came to an end.

Maria Theresa was thus the wife of the emperor and then the mother of the emperor. It is worth adding, however, that the title of Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (962 – 1806) had a rather symbolic meaning in their time – unlike in the Middle Ages, when the Czech king Charles IV was the emperor. (However, this was not essential for her in the exercise of power because, as the Czech queen, she was not subordinate to the emperor in any way.)

Charles IV is generally called the Father of the Fatherland. These words of appreciation, which were used to describe important monarchs in the Middle Ages, were first uttered about him by Vojtěch Raňkův of Ježov, professor and rector of the Sorbonne in Paris at Charles’s funeral, in a eulogy over the coffin. The designation of Charles IV as Father of the Fatherland has since entered everyday speech and this most crucial Czech king is called by this name to this day.

Maria Theresa would rightly be called the Mother of the Fatherland. She is not called that, but she was called the Mother of Europe, or also the Mother-in-law of Europe and the Grandmother of Europe. This is because she very strategically applied a marriage policy to her children. (Probably the most famous in this sense is the story of her daughter Marie Antoinette, the wife of Louis XVI – both were executed during the Great French Revolution.)

However, Maria Theresa (1717 – 1780) and Charles IV (1316 – 1378) are connected by an interesting coincidence of numbers:

- their birth dates were only one day apart. Charles was born on May 14, Mary on May 13

- both died on November 29

- and they lived to an age that was only one year apart. So Charles was 62 years old and Mary was 63 years old

Is it a coincidence or does Czech history have such a sense of humor?

Using information from the books by Jana Jůzlová and Radek Diestler: Czech History in a Nutshell, Great Monarchs of Europe