The end of World War II meant not only freedom for Czechoslovakia but also a relatively rapid road to unfreedom. At the end of this road was the communist putsch on February 25, 1948 and the ensuing 41 long years of totalitarian regime.

Czechoslovakia was established on October 28, 1918, after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The common state of Czechs and Slovaks ended on March 14, 1939, when Slovakia declared independence and became an ally of Nazi Germany. This happened after Hitler had threatened Slovakia that if they did not comply with this demand, Hitler would give Hungary a free hand to occupy Slovakia. Just a day later, Hitler forced Czech President Emil Hácha to agree to the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

After the war, the common state of Czechs and Slovaks was restored on the basis of the theory of the legal continuity of Czechoslovakia – but without the territory of Subcarpathian Ruthenia, which was ceded to the Soviet Union. The period of the so-called Third Republic began, which was only a formal democracy and an open road to totalitarianism.

Intimidation, Expropriation, Political Trials, and Executions

Totalitarianism is a will implemented by force, regardless of the opinions of the voters and the principles of democracy. To make such a thing possible, it is necessary to either silence, or intimidate, or eliminate the supporters of democracy. The others are then treated in such a way that they become a silent majority.

It was no different in our country. A period of political trials and repression ensued. Opponents of the totalitarian regime were executed or sentenced to long years in prison or to work in the uranium mines in penal labor camps. (Czech uranium was the subject of the highest political interest. It belonged to the Soviet Union by virtue of a secret agreement made as early as November 1945. This was because the USSR needed uranium for its atomic bomb, and ore from the Czech Ore Mountains was the most easily accessible.)

Opponents of the regime had their property confiscated, and they were forcibly displaced. The regime also took harsh revenge on national heroes – people who fought for the freedom of their homeland during the war and were willing to give their lives for it. Soldiers who served as RAF pilots during the war were put out of service, imprisoned, and tortured.

General Heliodor Píka was falsely accused of spying for Great Britain and hanged in 1949. Just a year later, politician Milada Horáková, convicted in a monster political trial, was hanged. General Karel Kutlvašr, who led the Prague Uprising in May 1945, was sentenced to life in prison for high treason. The innocent priest Josef Toufar died after four weeks of brutal torture, which was part of the persecution of churches and the liquidation of religious orders.

All four were fully rehabilitated after 1989. All four received high state awards; Heliodor Píka and Karel Kutlvašr received the highest, the Order of the White Lion. The day of Milada Horáková’s execution, June 27, has been named the Day of Remembrance for the Victims of the Communist Regime.

All victims are commemorated by the Memorial to the Victims of Communism, which speaks in precise numbers. Victims of Communism 1948 – 1989: 205,486 convicted – 248 executed – 4,500 died in prisons – 327 died at the border – 170,938 citizens emigrated.

Protecting Borders From Its Own People?

Every state protects its borders – but only totalitarian states use border protection to prevent their citizens from leaving the country. After the war, Europe was divided by the Iron Curtain, which isolated the nations of the Eastern Bloc from the free world. The first to use this term was Winston Churchill in March 1946 in his famous “Iron Curtain Speech” in Fulton, Missouri. The same Winston Churchill, who realized how dangerous it might be if the countries of the future “Eastern Bloc” fell into the Russian sphere of influence, asked the Americans to liberate Prague. This was said although it was originally agreed that the American troops would end at the line Rokycany – Písek – Český Krumlov (including Pilsen). Then, there was an attempt to agree with the Russians that the Americans would go as far as the Vltava and Elbe rivers, but the Russians refused.

Winston Churchill tried again on May 7, when he wrote directly to the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, General Eisenhower: “I hope your plan will not deter you from advancing on Prague if you have troops and do not meet the Russians first.”

That didn’t work either. We fell into the Russian sphere of influence with all the consequences. The fact that Pilsen was liberated by General Patton remained only in the memories of eyewitnesses, and official propaganda until 1989 claimed that the whole of Czechoslovakia had been liberated by the Soviet army.

Restrictions on freedom of movement appeared just two days before the communist putsch in February 1948. Passports were suspended, and it was impossible to travel normally outside Czechoslovakia. Then, freedom of travel was completely banned, and the regime decided who would be allowed to “go out” and who would not.

Borders had been guarded since 1945, especially those with Germany. This was initially presented as protection against Sudeten Germans, who had been deported to Germany after the war. Many of them had returned across the border to retrieve their property. (Over two million people were deported in total, and they were only allowed to take 50 kg of possessions per person.)

Border protection was originally seen as protecting the communist regime from the infiltration of agents from outside. However, given the development of intelligence operations, it became increasingly clear that the main reason for putting up wires along the borders was the fear of Czech emigration, i.e. the fear of free movement out of the country.

A border zone was created, up to 20 km wide, where entry was only possible with special permission. Politically unreliable residents were evicted from this zone. A forbidden zone was defined starting at two kilometers from the border. All residents were evicted from there, and almost all buildings were demolished to make it difficult to navigate the terrain. There were three rows of wire barriers directly on the border, the middle one of which was electrified. In the years 1952-1957, minefields were created in the zone between the walls of the barrier.

Action “Stone” and Pole Vaulter

After February 1948, many people tried to leave. Many of them chose to cross the border into the American occupation zone in Germany. Some then became victims of the provocation called Stone.

A fake border was set up before the actual state border. After crossing it, the refugees were stopped by a fake West German border patrol and taken to the imaginary office of an American counterintelligence officer. There, the people who believed they were already in the free world were interviewed. They were asked about the details of their escape and also asked to reveal any possible collaborators. After providing the information, they were taken back into Czechoslovakia and sentenced to prison.

Part of the border protection was also a control strip – a 15-meter-wide strip of plowed and dragged land where the traces of border intruders would be visible. This strip once became fatal for one person who was an active athlete, a pole vaulter. He jumped over the wire barriers – he had the pole on a rope, and after hitting the ground he always put it under the wires. But he could not vault in the plowed soft ground. He could not run properly to get over the wires on the pole. After many attempts, he was left lying exhausted on the Czech side of the border…

King of Šumava? No, I’m Pepík.

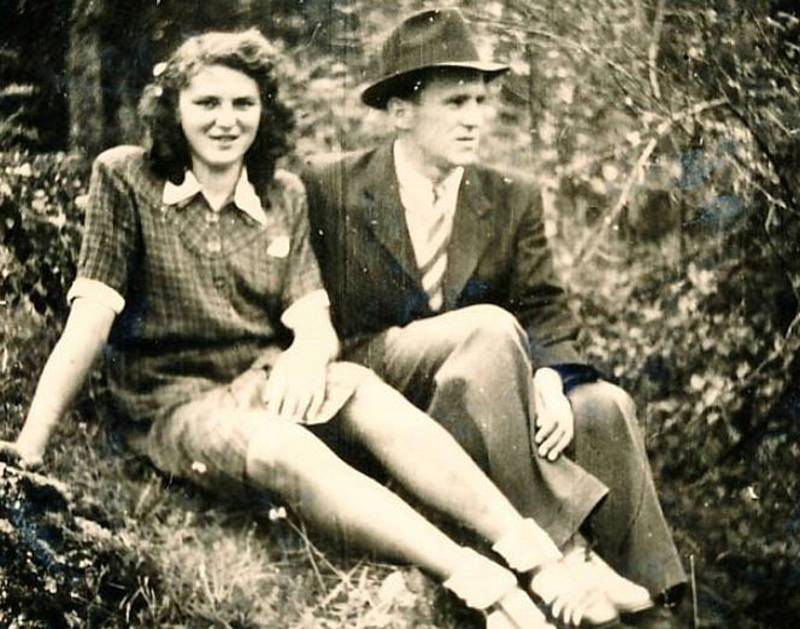

One of the people who helped people leave the wired-in country was Josef Hasil, who became a legend because of this.

Josef Hasil was born in 1924 in the tiny Šumava village of Zábrdí (even today the village has only 64 inhabitants), 25 km from the German border. He was the seventh of eight children in a family without a father: “It was certainly hard for my mother as she was the only one to look after us, but my father was a drunk and beat her, so we were better off without him.” As a child, he herded geese for money and worked for farmers: “My mother took care of me as best she could. We had to help her – we went to serve. At the age of five, I had to go to the next village to herd geese. If I had wanted to run away, I wouldn’t have even found my home.” The poor family stuck together, and the siblings helped each other. The willingness to help is very evident in Josef Hasil’s story.

He trained as a shoemaker, and during the war, he was forced to work in Germany. (Totaleinsatz – residents of occupied countries were forced to work in Germany, which was struggling with a labor shortage due to conscription; at the beginning of 1943, five million people worked in Germany, and 640,000 Czechs were deployed during the war.) In March 1945, Josef Hasil fled to Bohemia, where he hid in a cave until the end of the war and worked as a liaison for the partisans. He and his brother also disarmed German soldiers who were fleeing the protectorate and stole bicycles in villages: “My brother told them: ‘Come listen to the radio!’ So they went to a farmer and reported that the German army was surrendering. They were then willing to surrender to the Americans.”

After the war, the twenty-one-year-old Josef joined the army, became a National Security Corps member, and graduated from police school. After that, he served in the garrison in the village of Zadní Zvonková (Glöckelberg), on the border with Austria. He commented about this village: in 1923, it had five inns, three shops, two newsagents, a mill, a hammer mill, a school, a sawmill, and a church. In 1930, Zvonková had over 600 inhabitants.

After 1948, it was razed to the ground as part of the construction of a forbidden zone along the state border, where no one was allowed to live, nor were any landmarks allowed to be left there – houses, chapels, churches, cemeteries.

And because propaganda plays a big role in the totalitarian regime, this was done with the constructive slogan: “We are building a republic; we are happily cleaning Šumava from Sudeten remains.”

But then came a turning point in Josef Hasil’s life. After the communist putsch and the death of Jan Masaryk, he realized that he was on the wrong side of the barricade and began to transfer refugees to the West. (Jan Masaryk was the Minister of Foreign Affairs, the son of the first Czechoslovak president, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk. On March 10, 1948, he was found dead under the windows of his apartment in the Černín Palace, the headquarters of the ministry, where he lived. The official version was suicide, but many inconsistencies spoke against it. Today, after many new investigations into the story, it is essentially certain that Jan Masaryk was thrown out of the window.)

Even before this decision, while still in police service, Josef Hasil respected personal freedom, letting many groups of refugees pass and even advising them where to go. However, in the autumn of 1948, someone reported on him. He was caught and sentenced to nine years in prison for anti-state activities. He was sent to prison by the infamous prosecutor Karel Vaš, who had just put General Heliodor Píka on the gallows.

Josef Hasil managed to escape from prison after a few months and, after a month of secret stay at home, he and his brother Bohumil decided to flee to Munich, where they enlisted in the services of the American intelligence service CIC (Counterintelligence Corps), the predecessor of the CIA.

An excerpt from the story of his escape: The young men were running towards Pilsen. They could go no further. They were suffering from blisters; they were all wet and tired. They came across a small house in the forest. “So I said to Tonda: ‘Tonda, wait here behind those trees.’ It was morning, just before seven o’clock. I just opened the door, and there was a woman. I tell her: ‘Don’t be angry; we’re not criminals; I’m a member of the National Security Corps; I escaped from prison; they only locked me up because I was smuggling people across the border.’ And she says: ‘Hey, come on in, we have a son, and he wants to run away too, and we don’t know if he’s done it yet or not.’ And right away, the ranger was there; he came to her and said: ‘Come in, don’t be afraid of anything.’ They helped us a lot, they treated our feet with some oil they have for animals, we washed ourselves properly, gave us food and we waited until evening. And in the evening, we made an agreement; the ranger said: ‘I have a place here in the forest where you can hide; only the gypsies know about it; they go there to give birth.’ They gave us new shoes and food and at night they took us there.

Professional People Smugglers

Under the wings of the CIC, the brothers were no longer voluntary smugglers, but agents who returned from Germany to Bohemia to build intelligence networks there. They set up dead drops, carried leaflets, and smuggled radios. They were later to identify places for paratroopers to jump in the event of a military conflict between the democratic West and communist countries. On their return journeys, they smuggled people persecuted by communists across the border. All this until 1953, when the border was sealed off by the Iron Curtain.

Josef Hasil was not the only smuggler on the border, nor did he have the largest number of smuggled people. But he was the one who bothered the totalitarian regime the most. That is why the communists began to call him the King of Šumava, although he himself always said that he was not, that he was simply Pepík (that is the folk variant of the name Josef). They blamed him for the death of the nineteen-year-old border guard Rudouš Kočí in a shootout at the Soumarský Bridge, although it was later proven that Josef Hasil was not to blame for his death. And it was also because he provoked them. For example, he would leave them written messages: “I passed through again.”

(Interestingly, during the entire duration of the Iron Curtain, only twelve soldiers died in direct clashes with pedestrian agents. However, a total of 600 soldiers died guarding the border, 200 of whom committed suicide.)

When he last secretly met with his mother, she told him: “I would rather see you in a coffin than fall into their hands again.” That’s why he had a phial of poison ready so they wouldn’t take him alive. But his faith always helped him. “I mainly pray to the Virgin Mary; she’s my protector. When I went to Bohemia, I prayed: Virgin Mary, if I do good, protect me, and if I don’t do good, let them kill me! She always helped me and I stayed alive.”

He managed to escape from all the traps, but his brother Bohumil was shot while trying to get his one-year-old son across the border. At the time of his arrest in 1948, he himself was three weeks away from marrying his pregnant fiancée, Marie Vávrová. Later, as a CIC agent, he wanted to get Marie over to the West, but she was afraid: “We agreed on a place and time, but she didn’t arrive.” His son Josef Vávra only saw him after the Velvet Revolution.

Paradoxically, his son was contacted decades later by a man from Volary who had formerly worked as a border guard. He claimed to have had his father in his sights at one crossing. Josef Vávra said: “But dad was just leading women and children, so he let him through. In the early 1950s, most soldiers and border guards were cheering for dad anyway. When word got out that Hasil was supposed to be approaching the border, they kept their fingers crossed for him. It only changed when hardened communists, brainwashed from political training, arrived at the border.”

Because the communists failed to catch Josef Hasil, they took revenge on his family. In the summer of 1950, they sentenced 96 of his family members and associates to life imprisonment or decades in prison. Including his mother and fiancée, so his son grew up without a mother for many years.

After the Iron Curtain closed, Josef Hasil went to the USA. He washed dishes, worked in a butcher shop, and made a living as a carpenter. He was a draughtsman at the General Motors factory for thirty years. In 1972, he wanted to go to the Munich Olympics. Shortly before his departure, he learned that the communist state security had set a trap for him. They wanted to kidnap him and take him back to Czechoslovakia, where they would execute him.

As his son later recounted: “He was still terribly afraid of the communists and was afraid to come here. He told me that he was afraid that they would shoot him there. Until his death, he would wake up at night from his sleep because he dreamed that the communists were chasing him.”

On the national holiday of October 28, 2001, President Václav Havel awarded him the Medal for Heroism. Josef Hasil died in November 2019 in Chicago, at the age of 95.

The Last Movie So Far

The story of Josef Hasil has been depicted in art several times. So far, the last person to be interested in him was director Kris Kelly. This resulted in a feature-length, partly animated documentary, Kings of Šumava. It features not only Josef Hasil but also one of the women he once took across the border. She ardently declared: He saved my life.

Director Kelly is Irish, and his life experience made him interested in the topic: “I come from Belfast, where we have long-term problems historically; now with Brexit, in the past with violence, conflicts, and war, all of which are and have been related to borders.

Sometimes, you need an outside perspective – and that’s how I approached Kings of Šumava. The aspects of borders and their meaning are very important and close to me. As a native of Belfast, I identify with Northern Ireland, and that’s a very difficult position to be in at times.

As someone from another country, I was shocked by what Hasil’s family had to go through. Even though my country also has a complicated past, it was shocking to me. I gradually began to realize who the real heroes are and where bravery and heroism come from. That was the exciting journey of filmmaking.”

With thanks for the information: Memory of Nations