Although the National Monument on Vítkov is one of the sixteen buildings of the National Museum, it cannot match the popularity of its other buildings, starting with the historic building on Wenceslas Square. And it is not really its fault. The reasons are: its excessive size and the mummy of the “workers’ president” Klement Gottwald.

Let’s look back in history for a moment.

In 1948, a communist putch took place in our country, thanks to which the then communist Prime Minister Klement Gottwald became President. There was a great terror against opponents of the regime and the destruction of democracy, all under the leadership of Stalin`s advisers.

In 1953, Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin died. When Czech President Gottwald returned from Moscow from his funeral, he complained of nausea and died just nine days after Stalin. His wife, Marta Gottwaldová, repeatedly mentioned that he had been poisoned in Moscow, but it turned out that he had died of severe alcoholism and untreated syphilis, which caused an aneurysm.

After Gottwald’s death, the Czechoslovak communists decided to turn him into the mummy, like Russian communists had made with Lenin in Moscow. The communist president was embalmed and exhibited in the mausoleum. His mummy was placed in a glass sarcophagus and people had to go to see it.

Where? The mausoleum was built in a part of the monument at Vítkov – it also included a columbarium for many other prominent figures of the communist regime.

Strangely enough, even Stalin’s and Gottwald’s deaths did not stop work on the preparation of the monstrous Stalin monument on Letná. It was unveiled in May 1955. The figures were 12.5 m (41 ft) tall, and the monument was at the time the largest group sculpture in Europe and even the largest Stalin statue in the whole world.

Although Czechoslovakia had plenty of economic problems at the time, not only as a result of the war, but because of the destruction of private business after the communist putch, this monument cost an incredible amount of money – the equivalent to $200 million today. The regime was so ridiculous that because of the monument, he even turned the statues of angels on Chekhov Bridge to look in the same direction as Stalin…

Stalin’s monument was derisively called “the meat queue” and was despised by all but staunch communists.

Neither of these “historical excesses” lasted long, only a few years. In 1962, the body of communist president Gottwald was cremated, the columbarium was removed and Stalin’s monument on Letná was blown up. And during the reconstruction in the 1970s, even the angels on the Chekhov Bridge were turned back to their original direction.

However, the excessive size of the Letná memorial, comparable to the mocked Stalin statue, and the history of the mausoleum of communist notables, are the reasons why Czechs do not have a very warm relationship with the monument in Vítkov.

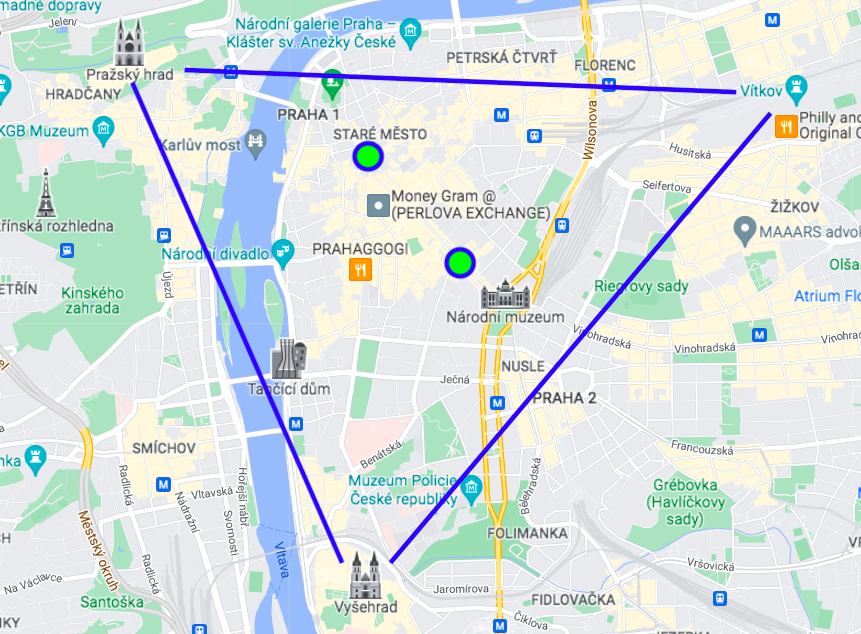

Regardless of the fact that this functionalist monument has nothing to do with communists at all. It was built in 1929-1933 to honor the memory of Czechoslovak legionnaires and the Czechoslovak resistance during the First World War. It was intended to emphasize the pride and courage of the Czech nation and was to be as dominant a landmark of Prague as Prague Castle and Vyšehrad (the green-blue dots on the map indicate Old Town Square and Wenceslas Square with the historic National Museum building).

And why was this memorial built right here?

Until July 1420, it was an ordinary hill called Vítkov after the Prague burgher Vítek of the Hill, who had his vineyards here. But then the hill became the scene of a great battle of the Hussite armies against the Crusaders. And the Hussites were commanded by one of the most famous Czech warlords of all time, Jan Žižka.

That’s why this part of the city was named Žižkov several centuries later, and why there is a larger-than-life equestrian statue of Jan Žižka on Vítkov. (If it were a statue of usual dimensions, the size of the monument would make Žižka look like a mini-figure on a rocking horse.)

This statue is the sixth largest bronze equestrian statue in the world. Weighing 16.5 tons, it is composed of 120 parts held together by 5,000 bolts. It was installed here in 1950.

The municipal district of Žižkov was named after the Hussite leader in 1877, when the municipality was created by separating from the original municipality of Vinohrady. They were separate towns, standing far from the walls of Prague, they became part of Prague only in 1922. It is worth remembering that in the middle of the 19th century Žižkov had only 197 inhabitants. Then came the rapid construction of new apartment buildings and in 1890 Žižkov had 42 thousand inhabitants, today it has 57 thousand of them.

The poor inhabitants of Žižkov often called it Žižkaperk. This is because German was the official language in Bohemia in the 19th century. It had been so unofficially since the Battle of Bílá Hora in 1620 (today Bílá Hora is part of Prague 6), and was mandated by law during the reign of Queen Maria Theresa (1717-1780). German was then not only the official language but also a sign of social status. Simply put, the poor uneducated people spoke Czech, the rich and educated German. Žižkov was therefore called Zischkaberg, from which was formed the Czech term Žižkaperk.

If you would like to go there, the best way is to get off the bus at the Ohrada station. (It is also named after a former farmstead – there was a vineyard of this name here in 1455). From Vítkov you can then go down to the right to Karlín, where there are many great cafés.

By the way – Karlín and Žižkov are connected by a 300 m long tunnel under Vítkov. It is open to pedestrians and cyclists and has two names. The inhabitants of Žižkov call it the “Žižkov Tunnel”. And the inhabitants of Karlín?

The “Karlín Tunnel”.

From Vítkov you can also see the Žižkov Television Tower and Church of Saint Procopius. Can you find where it is hidden in the second photo?