If houses could talk, this 250-meter-long house on Letná would tell a long, exciting story. It is no exaggeration to say that history not only paraded in front of its facade but also passed through it. It would be a story of architects who had to flee to the US or Ecuador while working on a project. And also the story of Jewish tenants who ended up either immigrating or in concentration camps. During the war, prominent Nazis lived here,who were then replaced by prominent communists after 1948. In November 1989, two people close to the dissidents persuaded the communist prime minister over a plate of cabbage soup to meet with Václav Havel for the first historic meeting.

Letná Plain Strategic, Political, and Cheerful

The plain in front of the house was first documented as historically significant in 1261, when Přemysl Otakar II was crowned King of Bohemia, and a coronation banquet was held on the plain. (That’s why the street that runs onto the Letná Plain on the side of the house is called Korunovační, i.e., “Coronation Street”.)

The plain in front of the house was first documented as historically significant in 1261, when Přemysl Otakar II was crowned King of Bohemia, and a coronation banquet was held on the plain. (That’s why the street that runs onto the Letná Plain on the side of the house is called Korunovační, i.e., “Coronation Street”.) In 1420, Sigismund of Luxemburg’s troops camped here when they besieged Prague. During another siege of Prague in 1648, there was a camp of Swedish troops. But at different times, French, Prussian, and Habsburg armies also camped there. Due to this strategic military importance and location high above the Vltava River and the center of Prague (the Old Town Square is visible from the edge of the Letná), the plain remained undeveloped.

The plain served many times as a stage for demonstrations of political power during the times when Czechoslovakia was a totalitarian state between 1948 and 1989. Regular military parades full of tanks, armored vehicles, flying helicopters, and other weapons that no normal person would be able to name were held here. Every year on May 1st, there was a monstrous Labor Day celebration, when crowds of people paraded in front of the tribune where the representatives of state power stood – although participation was voluntary, those who did not go could expect problems… Unfortunately, in August 1968, when the armies of the Warsaw Pact attacked us under the command of the troops of the Soviet Union, occupation helicopters landed on the Letná Plain.

However, the Letná Plain has its political significance even in the democratic part of our history. During the Velvet Revolution, ground-breaking demonstrations took place here – on November 25th, 750,000 people gathered here, and a day later, there were even more than a million of them. Letná Plain has this meaning to this day – in 2019, almost 300,000 people demonstrated here against Prime Minister Babiš.

However, the plain has also experienced many joys. In 1920, 70,000 Sokols trained here (at that time, the house did not yet exist; that’s why the Letná Water Tower can be seen behind the grandstand with spectators); in April 1990, Pope John Paul II celebrated mass at Letná. It is also interesting that in September 1996, Michael Jackson chose Prague for the start of his world tour for the HIStory album. During that time, his larger-than-life-sized statue stood on Letná on the pedestal, which was left here after the blown-up statue of the dictator Stalin – what a paradox!

(Photo)

The House and Its Builders

Initially, 14 separate houses were to be built here (one was planned as a semi-detached house, so the house has 13 orientation numbers). Because of its size, the house was already called Molochov at the time of its construction, after the word “moloch” (one of the meanings of this word is the designation of something huge, cumbersome, reacting about as quickly as an ocean liner when it discovers that it has forgotten something in the port and decides to turn around on the high seas).

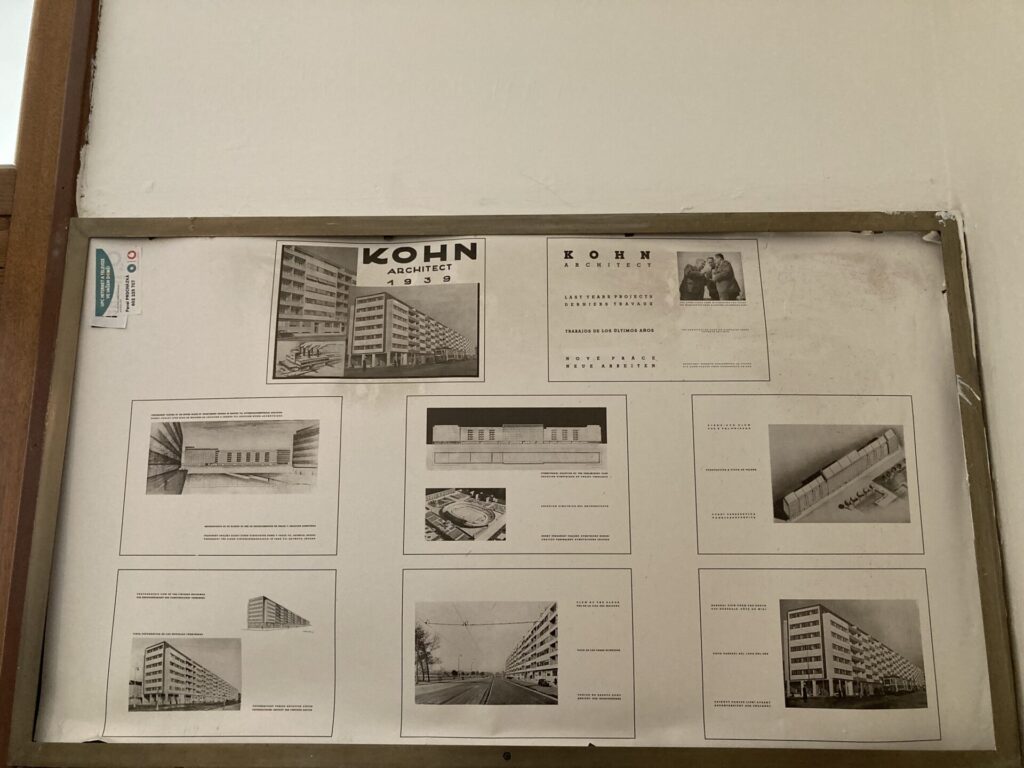

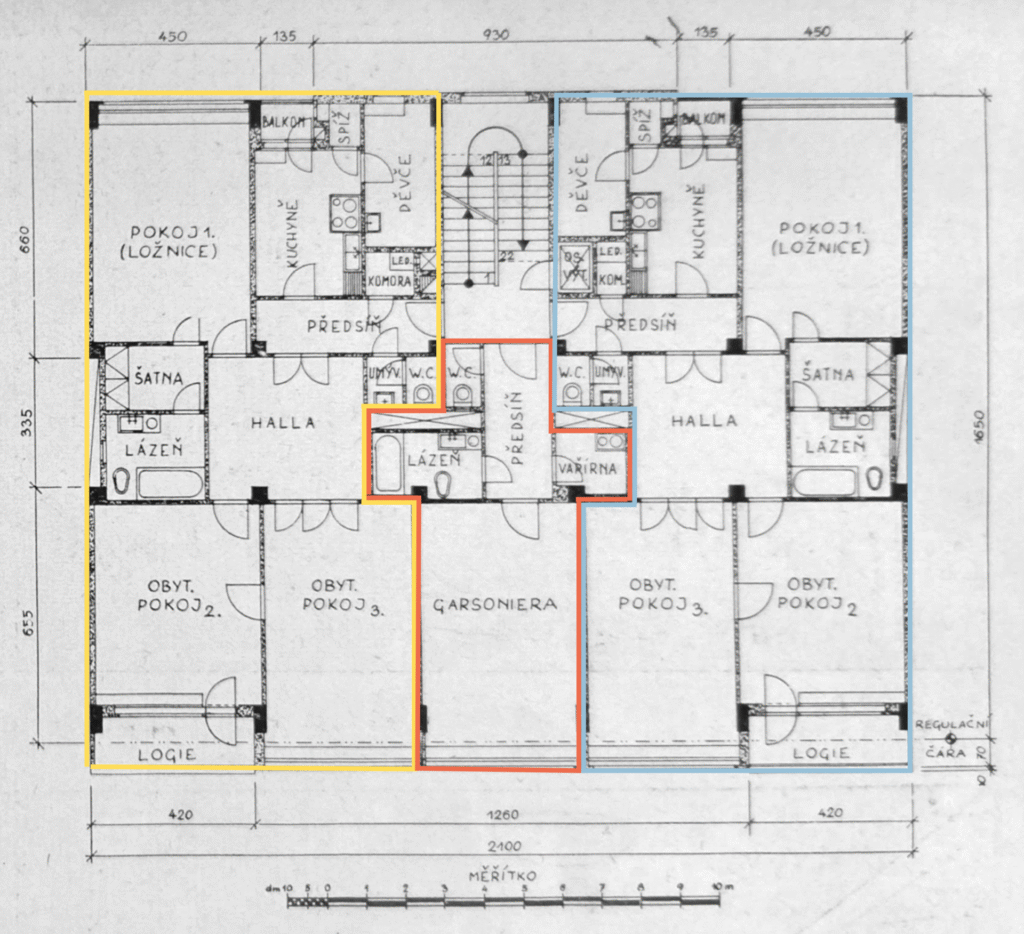

The construction took place in the years 1936-1938; the architects of the individual houses were Josef Havlíček, the brothers Otto and Karel Kohn, Leo Lauermann, František Votava, and the architects Arnošt Mühlstein and Victor Fürth, who worked together. Seven of the thirteen houses were to be designed by the Kohn brothers; therefore, their task was also to unify the facades of the houses. But in the end, it was decided to build a combined luxury functionalist house of wealthy tenants with strip windows, a flat roof, ceramic tiles, a white facade, and entrance doors in travertine-clad portals. However, the houses have different layouts and details on the staircases and vestibules – according to the design of the individual original houses’ designers.

Flats

Molochov was one of the so-called electric houses that was built in Prague in the 1930s. This was generally the name given to modern houses built in a constructivist or functionalist style. They had an unadorned facade, mostly with strip windows, so their apartments were very bright. The houses were fully electrified, and the flats had toilets and running water, which was not yet commonplace in the period between the world wars. The houses were no longer heated with wood and coal, so they were clean, and there was no fire danger.

However, the most beautiful apartments were on the top floor, which protruded out a bit from the facade, where the residents also had a large terrace at their disposal. The apartments are of various sizes, from the smallest one-room apartments for former caretakers to ten-room apartments over the entire floor.

Oscar-Winning Director Miloš Forman and Molochov?

The Kohn brothers were of Jewish origin, which is why they had to flee from Nazism in 1938. More than twenty family members went to France and then to Ecuador. The brothers’ mother’s family stayed in Prague during the war and was murdered by the Nazis in concentration camps.

Specially, the house is connected with the fate of the Oscar-winning director Miloš Forman. His father Rudolf was a member of the resistance; he was arrested by the Gestapo in 1940, then imprisoned in Terezín, Buchenwald, and Auschwitz, and died of typhus in 1944. His mom, Anna, was falsely accused of distributing anti-Nazi leaflets, and the Gestapo came for her to her house. Ten-year-old Miloš had just fallen ill; his mother came to give him the same medicine twice in a row. Only later did he realize she had said goodbye to him this way.

In 1964, Miloš Forman received a letter from his mother’s fellow prisoner in the concentration camp. She told him that Otto Kohn was his biological father. The mother said she wanted him to learn the truth. Miloš Forman then wrote a letter to Otto Kohn, who confirmed this information but did not want to meet him. (Perhaps also because the births of Miloš Forman and Kohn’s legitimate son Josef, later professor of Mathematics at Princeton University, were only three months apart.)

Residents

The residents of the house changed according to the political situation. During the democratic First Republic, many wealthy Jewish merchants lived here. They had to – just like the Kohn brothers – flee or end up in concentration camps, and prominent Nazis and employees of the Reich film industry lived in their apartments. After the communist putsch in 1948, prominent communists and people from the nearby Ministry of the Interior settled here.

Čestmír Císař, a communist MP, diplomat, and minister, once considered for the post of president, lived here. The entire floor of one of the houses was occupied by Josef Smrkovský until 1968, who experienced a lot from his communist comrades – success, imprisonment, resurrection, and further damnation. Even two floors of one of the houses were occupied by Minister of Communications Karel Hoffman, who, on August 21st, 1968, prevented Czech Radio from broadcasting The Proclamation to All the People of Czechoslovakia, which condemned the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops. He gave the command to turn off its transmitters, and muted Czech Radio.

Alois Indra also lived in one of the houses, one of the authors of the so-called Invitation Letter written in Russian, which sent five prominent communists to Leonid Brezhnev in August 1968 – in the letter, they asked him for protection against the alleged impending counterrevolution, which became the pretext for the occupation on August 21st. 1968.

The House in November 1989

However, history came through this house henceforward. On November 19th, 1989, musician Michael Kocáb and lyricist Michal Horáček from the independent initiative Most (The Bridge) came here for a prearranged visit in an attempt to mediate a dialogue between the ruling communist regime and the dissent, whose most visible figure was Václav Havel. The person who they were visiting was Prime Minister Ladislav Adamec. He welcomed them in casual home clothes; his wife poured them a plate of cabbage soup.

On November 26th, a photo was taken that went around the world – at the first meeting in history, the head of the communist government, Ladislav Adamec, and the leader of the dissent, Václav Havel, shook hands. One month and three days later, Václav Havel became president.

Michael Kocáb became the chairman of the parliamentary commission for supervision of the withdrawal of Soviet troops. The last occupation soldier left Czechoslovakia precisely according to the agreed schedule in June 1991.

And the house? It still watches over Letná. It is a bit shabby because it has had too many owners, and they haven’t agreed on a renovation plan yet. Even so, you can see that it can be classy. And that it has really seen and experienced a lot. Just step inside, and elegance will breathe on you at every step. And it’s nice that the Kohn brothers are still remembered on the noticeboard at the exit of the house.

The apartments in Molochov were above standard disposition and facilities. The most common were apartments with a kitchen, a bedroom, and a maid’s room facing north and a large living room or, alternatively, two rooms with a view of Prague on the opposite side of the house. There is a hall and a spacious bathroom with an adjacent dressing room, a garbage chute, and a laundry room. As the hall was not directly lit, it was separated from the living rooms by a glass wall.

Molochov just after completion. The interesting thing about the photo with the car is that it drives on the left. In Austria-Hungary, they drove on the left, which was based on the ancient custom of horse riders riding on the left side of the road – most people are right-handed, so knights held their swords in their right hand and could, therefore, better defend themselves against the enemy. (The promoter of driving on the right was Napoleon Bonaparte, who was left-handed.)

We did join the Paris Convention in 1931 and undertook to introduce driving on the right within five years. It didn’t happen, so in 1938, there was a government decision to drive on the right from May 1939. After the invasion of Germany and establishing the Protectorate on March 15th, 1939, Hitler ordered an immediate switch to driving on the right. It happened overnight; Prague had nine days to “get used to it”.

The grandest entrance by architects Ernst Mühlstein and Victor Fürth is lined with white Carrara marble, and the entrance door is made of polished chrome.

This is what it used to look like on Letná during military parades. Molochov in 1980, hung with photos of Russian and Czech communist leaders.

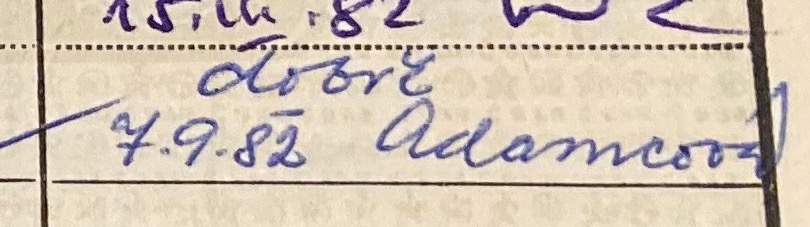

By the way – Zdeňka Adamcová studied chemistry at university and later taught at the same school. She was very nice to her students. She was in no way someone they feared and had a good relationship with them. This also says something.

The picture shows her signature on the report card of one of her students from 7 years “before the cabbage soup”.

Demonstration at Letná on November 25th, 1989. In the beginning, Marta Kubišová sings the “Hymn of the Velvet Revolution”, the song Prayer for Marta. It’s a 1968 song that begins with the rhymes: May peace remain with this land / Malice, envy, grudge, fear, and strife / Let them pass away, let them pass away / Now that the lost rule of your affairs / It will come back to you, people – it will come back. Václav Havel speaks after her in the video.

Moloch’s flat roof and its “political role”. During totalitarianism, members of the police stood on its roof; in democracy, photographers, journalists, and participants in demonstrations with flags.

On the podium, 1985. In front, President Gustáv Husák, behind him, Prime Minister Lubomír Štrougal, and one of the signatories of the Letter of Invitation, Alois Indra.

Where the tribune stood during military parades is today the Sparta football stadium.