One of the landmarks of Prague’s Vinohrady District is the Church of the Most Sacred Heart of Our Lord. The most important sacred building of the 20th century in the Czech Republic, which was built less than 100 years ago, is inspired by Noah’s Ark and has royal symbolism. The church stands on Jiří z Poděbrad (George of Poděbrady) Square, at the corner of which is a fountain called United Europe. And all of this is very closely related.

Královské Vinohrady and the Oscar for the film Amadeus

At first, there was a separate village called Viničné Hory (“vineyard mountains”), which was adjacent to Prague. It was renamed Královské Vinohrady (“royal vineyards”) in 1867; at that time, it was the fourth largest city in Bohemia and Moravia (1. Prague, 2. Brno, 3. Moravian Ostrava). Both of these names are related to the fact that there were extensive vineyards (Czech: vinohrady). The word “royal” then means that the local vineyards were established by the decree of King Charles IV from 1358, which was also supported by the restriction of the import of foreign wines to Prague from 1370.

In 1875, Královské Vinohrady was divided into Královské Vinohrady I and Královské Vinohrady II. A few years later, number I became Žižkov, and number II became today’s Vinohrady. As late as 1898, 70% of Vinohrady’s area was covered by fields, meadows, gardens, vineyards, and pastures. However, agricultural homesteads slowly disappeared, and the land was divided into parcels and replaced by urban development. The greatest boom occurred at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

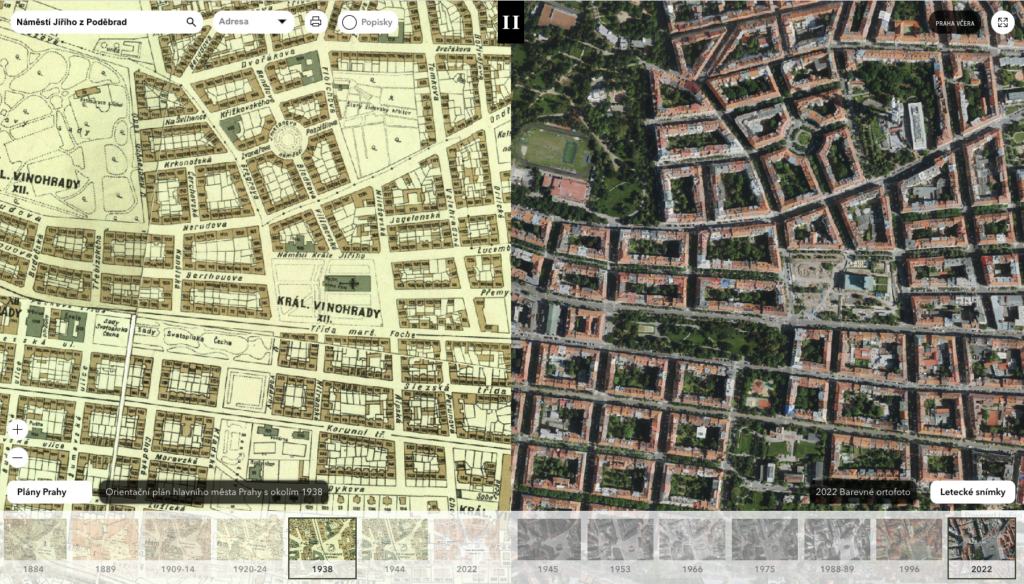

The development of Vinohrady can be compared nicely on maps. The one on the right is from 2022, the first map on the left is from 1884, and the second is from 1938. In 1938, we already saw continuous urban development, but in 1884, there were only fields, gardens, and vineyards. And also agricultural homesteads. Often named after their owners – Hofmanka, Vendelínka, or Švihovka.

There was also the Kravín (“cowshed”) homestead. First, there was a farmstead, then an inn with a dance hall, and a shooting range with a carousel for children’s entertainment. In 1868, a wooden theater arena was built in the inn’s garden, on whose site Jan Pištěk later built the famous “Summer Theater in Královské Vinohrady” and then the “Pištěk Arena in Slezská Street”, where theater was performed until 1932. His love for theater found its followers – his son Theodor was a film actor (he starred in a total of 325 films); his grandson Theodor is a significant movie designer, even boasting an Oscar for the costumes for the movie Amadeus directed by Miloš Forman; his great-grandson Jan is also a movie designer.

The Church as Noah’s Ark

As the city grew and the number of new houses increased, so did the number of residents of Vinohrady. And it was very quick – in 1880 it had less than 15 thousand inhabitants, in 1922 it had almost 90 thousand. Most of them were religious, 90% of whom were Catholics. And they needed their sanctuary. Services were first held in the school chapel on Belgická Street, later in the larger chapel of the Na Smetance School. However, even this was only a temporary solution. Therefore, the neo-Gothic Church of St. Ludmila was built on today’s Peace Square in 1893.

But Vinohrady did not stop expanding.

The development of Vinohrady progressed from the city center. So, while the Church of St. Ludmila had been standing on Peace Square since 1893, just 2.5 kilometers away it still looked like this in 1926 (the photo shows the Horní Stromka homestead, between today’s Flora and Želivského metro stations).

Therefore, the capacity of “Ludmila”, as the church is still familiarly called, soon became insufficient. In 1896, King George Square was created, today King George Square of Poděbrady. In 1908, it was decided that a new church would stand there. Until then, the city had lent the local parish a chapel in the new school building on the square’s north side. On the last day of 1913, the anniversary of the canonization of St. Alois, the patron saint of youth, the chapel was consecrated and named after him.

A competition was announced for the design of the new temple, in which the Slovenian architect Josip Plečnik won. However, he did not take part in it (at that time, at the request of the president of the TGM, he was the first official architect of Prague Castle, and his students had entered him into the competition). Josip Plečnik drew up three projects that differed in financial demands. The first design assumed a generous construction of the space with additional buildings, including a school, residential buildings, and a triumphal arch. The last design had about a third of the construction budget than the first. It is certainly worth mentioning that the architect himself did not want anything for his work. Although he could have asked for a fee of one hundred thousand crowns for the last project, the architect donated it to the temple free of charge.

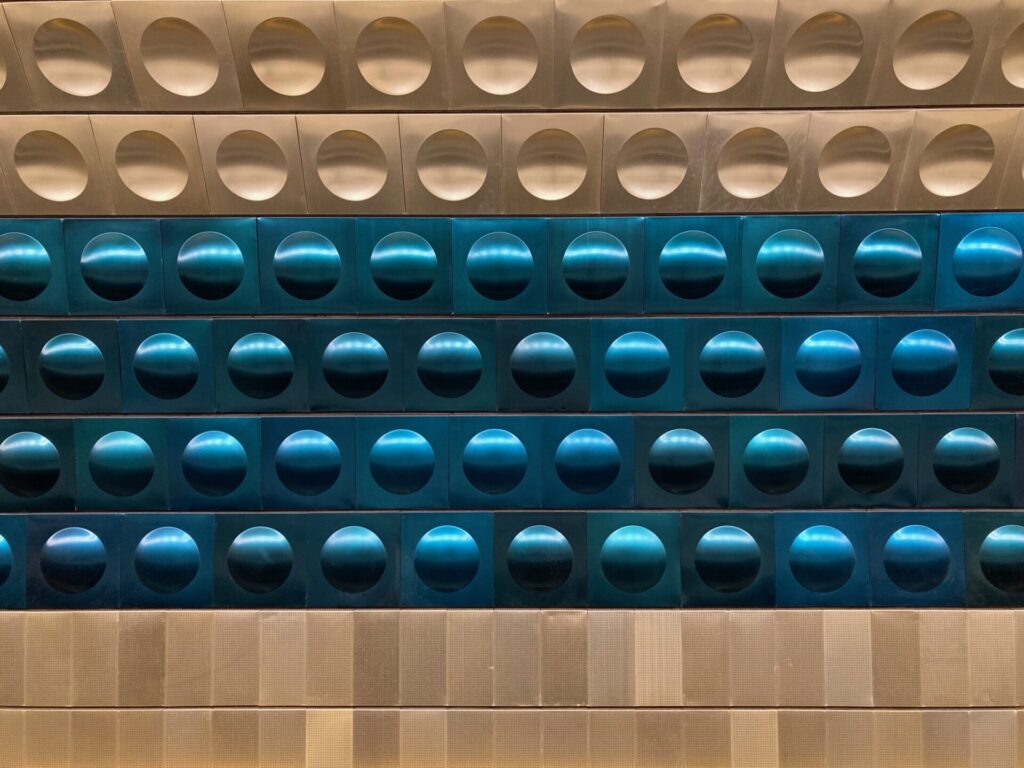

Plečnik was inspired in his project by the roots of Christianity, the ancient Christian liturgy, and its symbolism. He combined these with purely Czech elements referring to the time of Charles IV. The interior walls have a surface of unplastered bricks, on which several gilded crosses are regularly placed. The coffered ceiling of the church is made of polished wood. The exterior walls of glazed bricks are interspersed with bricks of artificial stone. This arrangement is intended to represent the purple-red royal cloak decorated with ermine.

The building permit was issued in early October 1928. Then someone thought that a second Vinohrady church could be a suitable commemoration of the 10th anniversary of the proclamation of the republic. Therefore, the church’s foundation stone was consecrated on October 28, 1928.

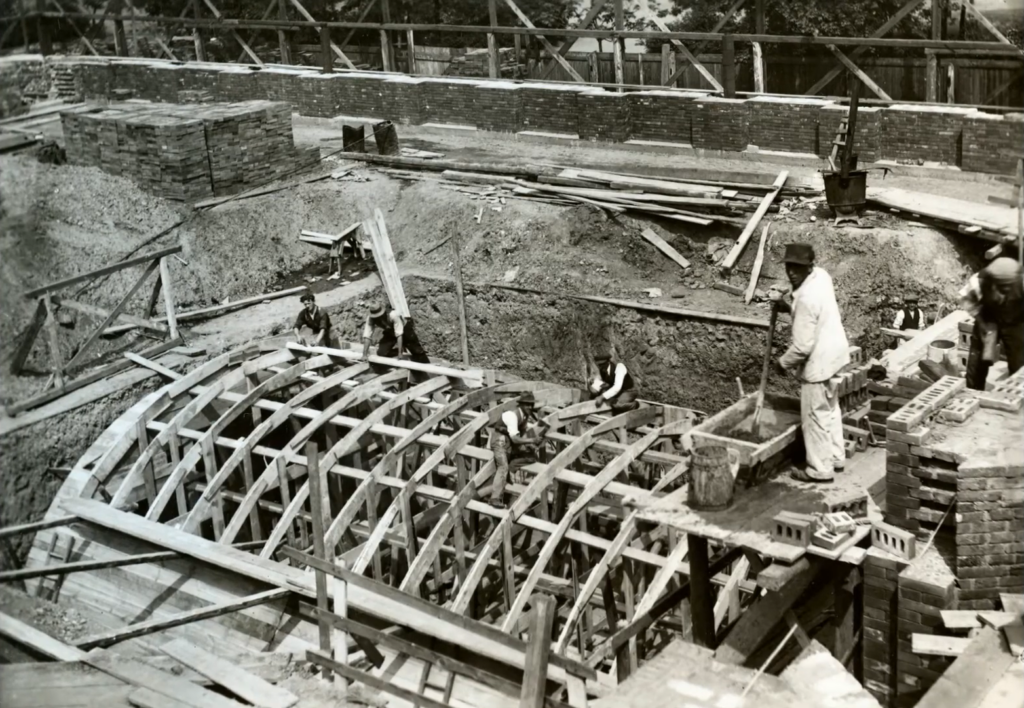

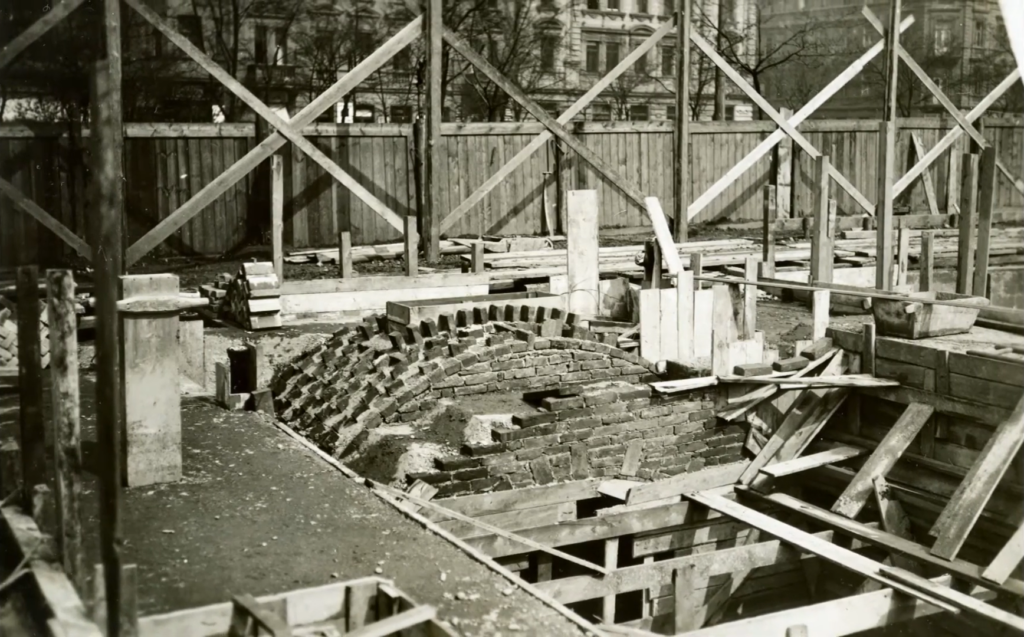

The first problems arose immediately when digging the foundations. There was a layer of loose fill to a depth of 5 meters, which was placed on less than a meter of original black topsoil, i.e. very high-quality soil. Underneath that was clay. However, solid rocky ground was not found even by drilling probes that went to a depth of 14 meters. Therefore, a reinforced concrete foundation slab had to be poured under the load-bearing walls and the church tower, up to 160 cm thick.

For example, 6,200 m3 of sand, 820 m3 of wood, or 1.3 million bricks were used to build the church. There was so much building material that if it were loaded onto a freight train, the train would have 500 wagons.

The estimated cost of building the church was two million crowns, and the unexpected foundation slab alone increased it by 700 thousand. The entire construction ultimately cost 4.8 million crowns. The money was obtained gradually and not always easily. Even though the municipality donated the land for the construction, because it itself had acquired it as a gift. And even though a significant part of the money was provided by the foundation of Karel Leopold Bepta, a councilor of the New Town who came from a wealthy family and owned many fields and vineyards in the Vinohrady area. He had no descendants, so when he died in the mid-18th century, the foundation mentioned above acquired his property.

An unknown benefactor contributed a total of 300 thousand crowns (it later turned out that he was Vladimír Slavík, a professor of forensic medicine at the Faculty of Medicine of Charles University and the rector of this university in 1928-1929).

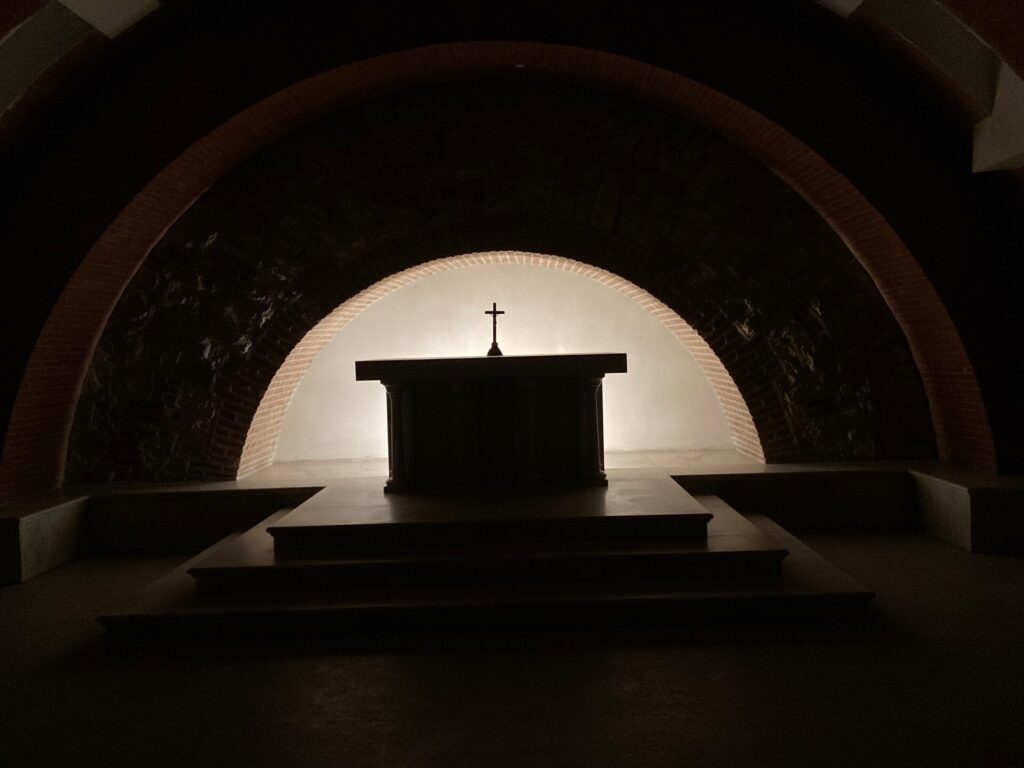

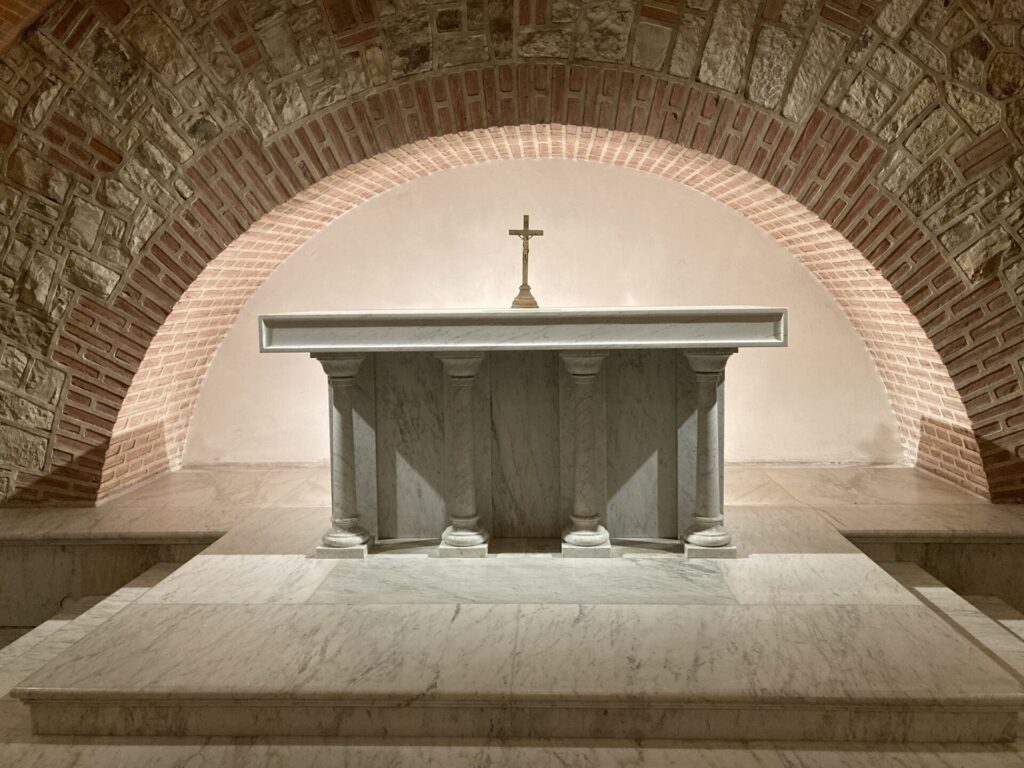

In the basement of the church there is a crypt, for the construction of which architect Plečnik used masonry demolished during the renovation of the Prague Castle grounds for President T. G. Masaryk.

In September 1931, the Vinohrady freight forwarder Karel Ronovský told the parish office that he had ordered six bells from the Brno bell-maker Manoušek at his own expense. Five of them were requisitioned during the war and melted down for cannons, leaving only the sixth, a small death knell. (By the way, the Manoušek bell-making company was founded in 1900, and bell-making has been passed down in the family to this day. The family has a museum in Zbraslav, which you can visit.)

Additional funds were obtained from a lottery, which brought in 287 thousand crowns. Also, from collections, lectures, concerts, or theater performances – the proceeds were not staggering, but it is not for nothing that the Czech language has a saying for patiently collecting funds: “crown to crown.” The bazaar, the sale of symbolic paper bricks, or a house collection organized by women from Vinohrady also helped. Enthusiasm, dedication and the desire to have their own church of sufficient capacity helped.

In the end, everything worked out, and the church was consecrated on May 8, 1932.

Above the main altar hangs a three-meter gilded figure of Christ, flanked by statues of six Czech patron saints made of linden wood: St. John of Nepomuk, St. Agnes, St. Adalbert, St. Wenceslas, St. Ludmila and St. Prokop

Since 2018, the church has had a new altar made of Carrara marble. Interestingly, the church was built according to the design of the then-architect of Prague Castle, Josip Plečnik (collaborator of President T. G. Masaryk), and the new altar was designed by the later castle architect Josef Pleskot (collaborator of Václav Havel)

The Czech King and His Idea of the European Union

The square is currently undergoing revitalization. The metro station has been renovated, and the park layout of the square is also undergoing a major transformation. In the photo from the church roof, the United Europe Fountain can be seen in the upper left corner.

It has been on the square since 1981, and it is uncertain whether it will return. However, the reason why it is so named is interesting.

The Czech King George of Poděbrady (1420 – 1471), after whom the square is named, was not only the only Czech king who was not from the ruling dynasty but from the ranks of the local nobility but also the last Czech in the Czech throne. He was the monarch who first realized the importance of a strong Europe that was united or closely cooperating.

The Czech King George of Poděbrady (1420 – 1471), after whom the square is named, was not only the only Czech king who was not from the ruling dynasty but from the ranks of the local nobility but also the last Czech in the Czech throne. He was the monarch who first realized the importance of a strong Europe that was united or closely cooperating.

Therefore, he had a proposal for an international union of European monarchs drawn up, and its author, Antonio Marini of Grenoble, then traveled throughout Europe in 1462-1464 to gain support for it. The most important place in the organization was to be held by the French king, who at that time was Louis XI.

The acceptance of the project was ultimately thwarted by the attitude of the Holy Roman Emperor, and especially the Pope, who in turn excommunicated George in 1466, declared him dethroned, and declared a crusade against him. However, most of Europe received this rather lukewarmly. A sad parallel to the 21st century is that the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus was one of the greatest opponents of an agreement between European states. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán follows him in his view of a strong united Europe.

UNESCO listed the peace efforts of George of Poděbrady in 1964 (on the occasion of the 500th anniversary) as events of pan-European significance.