On the left bank of the Vltava, in the hills high above Prague, two buildings are within sight of each other, the largest buildings of their kind in the world. The first is Prague Castle, the largest continuous castle complex in the world. The other is the Strahov Stadium with an area of nine football fields and a capacity of a quarter of a million spectators. (The third largest stadium in the world is Michigan Stadium, with a capacity of 107,000 spectators; the sixth largest is the stadium of the FC Barcelona football club, the largest football stadium in Europe, with a capacity of 99,000 spectators.)

The Industrial Revolution, the Demolition of Walls, and the Transformation of Czech Society

The 18th century brought many fundamental changes to the Czech lands and Prague. It all started with the Industrial Revolution. The textile industry was the first to develop in our country, followed by the sugar industry, porcelain production, beer production, and glassmaking. This was followed by the iron works, the engineering industry, the paper industry, and the chemical industry. At the end of the 19th century, the “Lands of the Bohemian Crown” were the most industrialized part of Austria-Hungary.

In 1845, a railway was introduced to Prague. Due to the trains’ arrivals, the city walls had to be breached, and a gate was set up, which was always locked at night. The trains arrived at what is today known as Masaryk Station. At that time though, it was simply called “Prague” because there was no other railway station in Prague. (Today, it is the oldest still-functioning terminus station in Europe.)

In the 1870s, the walls around Prague began to be demolished. Whole new districts, residential houses, and factories began to be built on the plots of land “behind the walls,” where previously there were only orchards, farms, and vineyards. This is how Vinohrady, Žižkov, Smíchov, and Karlín began to emerge.

People from the countryside moved to Prague in droves for work and had to adapt to a different lifestyle. The result was the emergence of a new social class, the workers. They continued to flock here despite having to live in not very high-quality tenements, and their work was definitely not easy. (At first they were working 16, later 14 or 12 hours a day, and although child labor was already prohibited, 30% of children over the age of 13 worked 4-6 hours a day; the complete ban on child labor came in 1919.)

However, this new life of the new social class of workers in the city had one advantage. While on the farm they would have to feed the cattle daily and the cow would have to be milked morning and evening, there was usually no work in the factories on Sundays. This led to people starting to go on nature trips on Sundays. (Although we must not measure nature by today’s size of the city. Excursions “far outside the city,” e.g., to the White Mountain, which today is a few trams stops from the Castle, or from Strahov itself, were very popular.)

The Beginnings of Sokol (Falcon)

In the middle of the 19th century, the first gymnastics clubs began to emerge, initially German. The first Czech association for physical exercises was Sokol in 1862. The Sokols built their first gymnasium two years later. It was in the street that is still named Sokolská in their honor, within sight of the National Museum on Wenceslas Square. However, the Sokols could not have known this because the museum was built almost thirty years later.

The primary purpose of the Czech community of Sokol was not only to care for the physical fitness of the members of the association but also for cultural activities and the support of personality development. In connection with this, there was also education for national, racial, and religious tolerance, love for the homeland, and respect for our nation’s spiritual heritage. (Two of the main slogans of the Sokols were: “A healthy spirit in a healthy body!” and “The country in the mind, strength in the arm!”)

An important activity of the Sokols has always been publicly performed physical exercises, such as the Gathering. At this year’s event, a parade of 20,000 Sokols from 17 countries passed through Prague, and President Petr Pavel opened the rally at the stadium.

The first Gathering was considerably more modest. It took place twenty years after Sokol was founded in 1882. Its audience was only members of Sokol; it was more of a private affair. A parade of 1,600 Sokols passed through Prague at the time, and there were 696 trainees.

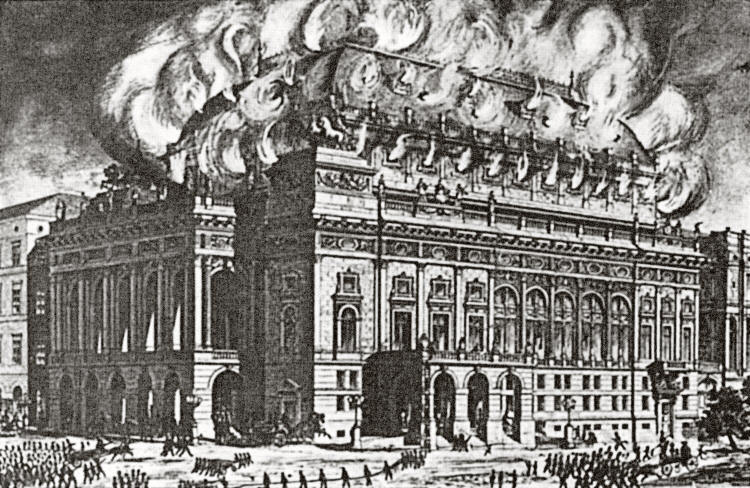

They trained on Střelecký Island (Archer’s Island), within sight of the National Theatre, which was not going through the happiest times at the time. It was opened in 1881 but almost completely burned down two months later. The backdrop of the meeting was only the burning site and the construction site (thanks to a nationwide collection and a great wave of patriotism, the National Theater was rebuilt within two years).

The 2nd Gathering, which was supposed to be organized in 1887, has an interesting link to the USA. At that time, the police only wanted to allow the appearance of trainees from Austria-Hungary. However, the Sokols didn’t like this, mainly because at that time, compatriots, the Sokols from the USA, were already on their way to Prague. Finally, the meeting was arranged in the town of Český Brod, 30 miles east of Prague. 40,000 people came to the city of 4,000 residents for the Sokol festival.

However, it was not a regular meeting but rather joint races of the Sokols. Therefore, the official second meeting was organized in 1891, on the occasion of the General Land Exhibition. At that time, they practiced in Stromovka Park, but even that was too small for the trainees. Further gatherings therefore took place on the Letenská Plain.

Even today, it is the largest free area for gatherings in Prague, which is why mass events have always taken place here. Under socialism, it was the pompous annual May Day celebrations and military parades. In 1989, the largest demonstration against the totalitarian regime was held here – 800,000 people gathered at Letná. Demonstrations of hundreds of thousands are occasionally held here even today if there is a reason for them.

The New Stadium

At the beginning of the 20th century, it was already evident that the Sokols would need their own stadium to organize gatherings. Even then, the neglected space in Strahov was considered. In 1925, an agreement was reached – Prague leased the land in Strahov for 80 years to the young republic, which undertook to finance the construction of a stadium for the Sokols. This is what happened and the first Sokol meeting was held there only a year later.

The stadium at the time was temporary but was roughly the size of the current one, which measures a respectable 202 × 310 meters (220 × 339 yd). There was a sandy training ground in the stadium area, which was lined with wooden stands. The stadium was gradually completed, and in 1932 it already had a presidential box. At that time, the stadium was named after President Masaryk, who came to watch the gathering from the Castle on horseback.

The Era of Spartakiads and Ideology on the Stadium

In 1948, the stadium hosted the XI—All-Sokol Gathering, conceived as a manifesto and protest against the incoming communist regime. The rally began in June 1948, just five days after the inauguration of Communist President Klement Gottwald, who came to power in a communist putsch in February 1948. At the time, 85,000 rally participants marched in the festive parade. At the time, the Sokols proclaimed the glory of the previous president, Edvard Beneš, and when the parade in the Old Town Square passed the tribune with Klement Gottwald, the Sokols turned their heads in protest and shouted: “We will not let ourselves be dictated to who we must love!” Two hundred Sokols were arrested during the parade, and further repressions followed. Sokol was a constant thorn in the side of the totalitarian regime with his ideals, so it was eventually banned.

However, the Communists took advantage of the people’s enthusiasm for joint public exercises and implanted their ideology in them. This led to the birth of the Spartakiads. (It should be added that on a tiny scale, these games, named after the mythical Spartacus, had been organized since 1921. And at that time, they were inspired by the Sokol gatherings but were organized by the communist branch of the workers’ physical education units).

It wasn’t immediate, and thanks to the incidents at the previous meeting, Gottwald did not want to follow the tradition of the gatherings. However, in 1953, Klement Gottwald died, and the first Spartakiad was held two years later as a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the end of World War II. Others followed in a five-year cycle until 1985. The exception was in 1970, two years after August 1968, when we were invaded and occupied for the next 21 years by Warsaw Pact troops led by Russia. At that time, the communists were worried that large gatherings of trainees (up to 1.5 million people prepared for the Spartakiad) could turn into anti-regime demonstrations.

As time passed, people forgot about Sokol, and most of those who trained at the Spartakiads did not perceive their ideological subtext despite the fact that it was always there. During the Spartakiad, mass exercises were held in every major city, but the highlight was the performance in Strahov. For many of the participants, this had other attractions than just the fact that they performed in the largest stadium in the world broadcast live by Czechoslovak Television. Among other things, there was the fact they had a free multi-day trip to Prague, for which they did not have to take a holiday. In addition, Prague was better supplied at the time of the Spartakiads, so participants from all over the country bought goods there that were in short supply in other regions. (Yes, it’s hard to explain a socialist trade system that was just a parody of a normally functioning market.)

Those who perceived the ideology the least were, paradoxically, the soldiers. They practiced at the Spartakiad compulsorily (for the other categories, it was called: “voluntarily compulsorily”). The soldiers had barracks full of ideologies, and this was a welcome addition to their regular military training. And if their unit was chosen to perform in Strahov, it meant two weeks of relative freedom for them in the capital. (This is also why more children were always born in Czechoslovakia nine months after the Spartakiad than in comparable periods of other years.)

There were 13,824 points at the Strahov stadium, one for each exerciser. The soldiers were able to run up to them and thus fill the entire exercise area in just 45 seconds. Many people still remember the Spartakiad in 1980, when the weather was very bad. The exercise was quite challenging for the soldiers, dressed only in white shorts.

After all, the “game for time” was an obvious part of the Spartakiad. Buses with trainees arrived at the area in front of the stadium according to an elaborate timetable. Stop – let people run out – quickly away so the next bus can come. Eyewitnesses confirm that at the last Spartakiad, the time for everyone to get off the bus was extreme – only 6 seconds.

The Future of the Stadium

The Strahov Stadium also experienced other events that required a large gathering area. In 1939, a military parade celebrated Adolf Hitler’s 50th birthday. During World War II, the Nazis used the stadium to gather Jews awaiting transportation to concentration camps. In May 1945, on the other hand, the stadium was an internment place for Germans who were waiting to be transported from Czechoslovakia.

But there were also happier moments. In August 1990, the Rolling Stones played in Strahov. For a country that had spent four decades behind the Iron Curtain, this was something quite incredible. That is why this concert is still associated with a strong emotion for many people: only then did they finally believe that the totalitarian regime had fallen.

It was a concert that was important for us, but also for the Rolling Stones, because Mick Jagger was a big fan of President Václav Havel. Keith Richards then said in one of the interviews: “Havel is the only politician I am proud to have met.”

The Rolling Stones played a wonderful two-hour concert in Strahov, and for free! The concert’s proceeds, more than four million crowns, went to the account of Olga Havlová Committee of Goodwill, which used the money for disabled children.

The Rolling Stones’ name is also associated with the Spanish Hall, the largest ceremonial space in the Castle. Here the president’s inauguration takes place. State honors are likewise awarded here on the October 28th national holiday. Lighting designer Patrick Woodroffe designed the new hall lighting, and the Rolling Stones paid for this investment.

In August 1995, President Václav Havel received the remote control for the lights from the musicians right in the hall. Ron Wood said at the time: “We also gave Havel the remote control with the Stounian tongue, and he was very excited. He said – I bet even Bill Clinton doesn’t have one. And you bet he doesn’t!”

The bands Guns N’Roses, Pink Floyd, and U2 also played in Strahov. In 1994, the XII. Sokol Gathering also took place here, even then with the participation of the president. This time, Václav Havel did not come from the Castle on horseback but by car. But gradually, it became clear that the stadium, whose stands can fit a quarter of a million people, needs to be continuously used in a meaningful way, and it must receive proper care. Today, Sokol is one of the largest organizations with 160,000 members. That’s a lot, but in the “golden age” of Sokol, there were almost a million of them. That’s why the stadium of the football club Slavia is enough for the Sokol gatherings.

One of the last major events in Strahov was the Mass celebrated by Pope John Paul II in May 1995.

No events have been held in Strahov for many years. The stadium mainly serves the football club Sparta, which has built a training area with eight pitches and a modern administration building there. However, representatives of various sports industries have their back offices there. You will also find a swimming pool, sauna, squash center, climbing wall, spinning, gym, and massage rooms inside the stadium.

But all this is a temporary solution because the stadium is rapidly deteriorating, and it is necessary to find some comprehensive use for it and, of course, ensure its repair. (The stadium is a cultural monument, but even that did not sometimes prevent the idea of demolition. However, that would not be so easy. Just a very rough estimate: 20,000 fully loaded trucks would have to take away the construction debris from Strahov.)

The Prague City Council wants the stadium to remain dedicated to sports, but other uses are also being considered – for start-ups, educational institutions or students (there are university dormitories for 5,000 students opposite the stadium). With a look at the crumbling reinforced concrete structure of the stadium, it is good to keep in mind the warning of construction experts who say that the stadium has about four years left. Then it would have to be completely closed because entering its stands would be too dangerous.

Acknowledgments: we thank Michal Šedivý and Open House Prague for the information and tour of the stadium.